Take Me to Church

Sunday was the first Sunday of Advent—for Christians the start of the liturgical year, marking the formal beginning of the Christmas season—and so I did something I’ve meant to do for a very long time: I went to church.

I was raised in a faith community—the United Church of Canada, in which I was christened as a young child and confirmed at the age of 14—and grew up going to Sunday school, singing in the choir, and doing community volunteer work as part of the church. For many years my family’s life revolved around the churches we attended—first Riverdale United Church in Toronto’s Leslieville neighbourhood and, later, Pickering Village United Church in Ajax Ontario.

Riverdale United Church, at least from 1976-1981 when we lived nearby and attended regularly, was as serious about its annual theatre productions as it was about the liturgy. The church community was intelligent in its interpretation of the Gospel, lighthearted in its practice of faith, and earnest in its commitment to public service. In many ways it has remained my model of a healthy, engaged, active church. Sadly, Riverdale United Church closed in 2010 after what appears to have been a long period of slow decline as the neighbourhood changed and long-time parishioners died or moved away. In 2018 the building, whose title had been transferred to the WoodGreen community services agency, was torn down to build supportive housing for seniors. I was fortunate to receive an invitation to salvage material from the building in the days before it was demolished, and am grateful to have one of the church’s stained glass windows and a hymnal cabinet—both pried from the building’s studs with crowbars I’d brought across town on the streetcar—in my home.

Riverdale United Church, at least from 1976-1981 when we lived nearby and attended regularly, was as serious about its annual theatre productions as it was about the liturgy. The church community was intelligent in its interpretation of the Gospel, lighthearted in its practice of faith, and earnest in its commitment to public service. In many ways it has remained my model of a healthy, engaged, active church. Sadly, Riverdale United Church closed in 2010 after what appears to have been a long period of slow decline as the neighbourhood changed and long-time parishioners died or moved away. In 2018 the building, whose title had been transferred to the WoodGreen community services agency, was torn down to build supportive housing for seniors. I was fortunate to receive an invitation to salvage material from the building in the days before it was demolished, and am grateful to have one of the church’s stained glass windows and a hymnal cabinet—both pried from the building’s studs with crowbars I’d brought across town on the streetcar—in my home.

Pickering Village United Church, which we attended from 1981 until 1988, was very suburban and, at least at the time, deeply stereotypically of various eighties excesses right down to the social cliques and rituals of conspicuous consumption. It was not a good fit for my parents, who were neither suburban nor middle class. Despite being treated as outsiders, my family contributed greatly to church activities—my father was a steward, my mother edited the church newsletter and served as choir secretary, we all sang in the choir (which was and probably still is excellent), volunteered for everything, and donated large sums of money my parents could really not afford—remaining active in the church until my father resigned us all from church membership over the at-the-time-divisive issue of gay ordination. This was a terrible pity, since my father, who had been reflexively homophobic like many of his generation, eventually came to support marriage equality because, perhaps above all, he was a romantic who believed in love. I don’t think he would, later on, have cared one whit about a minister’s sexual orientation or gender identity as long as they knew their theology and could slip a few ridiculous puns into a sermon.

As an adult I have, of course, gone to church / temple weddings and funerals and, sometimes, attended special services, but have never since belonged to a faith community. Most of the time this has seemed fine. Like my mother, I identify as a solitary Christian and have developed a deeply personal, rather unorthodox theology that remains principally Protestant in its structure but which seeks the divine (and divine revelation) in nature and natural processes—as, incidentally, do a great many deeply Christian hymns (more about one of my favourite hymns here). Since adolescence I have been agnostic about (even indifferent to) the divinity of Christ, while remaining committed to the Christian theology of sacrifice and redemption. In some quarters this would make me a heretic, but I’ve never had much patience for literalism. The God I believe in would appreciate it if humans thought more, not less, and would really like us to stop committing atrocities in His name. And along these lines, my favourite and most deeply valued para-religious texts include the anonymous fifteenth century lyric poem, “Adam lay I-bounden,” whose lines—“Ne hadde the apple take been, the apple taken been, / Ne hadde never our Lady aye been Heaven’s queen. / Blessed be the time that apple taken was, / Therefore we may singen, “Deo gracias.”—came as a revelation about knowledge and its gifts and responsibilities when I first encountered them in the good old Norton Anthology of Poetry in an undergraduate literature course; and Italian journalist Giovannino Guareschi’s book (made into a film) The Little World of Don Camillo, a series of interlinked stories in which a Catholic priest solves his village’s human problems in part by arguing with Christ on the Cross.

Sometimes, though, a solitary faith is a lonely faith and, as I’ve gotten older, I have longed to belong to a faith community. I’ve missed the rituals and fellowship and, perhaps above all, I’ve missed the hymns. Protestant hymns are, on the whole, joyful, rich in symbolism, and celebrate connections between the ordinary and the divine, and I miss hearing voices raised in song.

And so, on Sunday morning, on the first Sunday of Advent, I put on a nice dress and a good coat, and walked over to Runnymede United Church to attend my first Sunday morning service in more than three decades.

Runnymede United Church was established in 1925; the Gothic Revival building housing the congregation was completed in 1928. I’ve often admired the building while passing by—it’s right across the street from the elementary school my daughter attended for ten years, meaning that I’ve had plenty of opportunity to enjoy the architecture—and have noticed how often the building seemed abuzz with activity. In returning to worship, I have hoped to find a faith community neither too cliquey nor obviously in the process of dying out, and Runnymede seemed neither of these things. About a year ago I subscribed to the church’s email list, and was pleased to see a balance of traditional and contemporary interests represented in its regular communications. Because my church-going experiences are mainly from the 1970s and 1980s, I was hoping to find a church in which traditional elements of the liturgy had not entirely been discarded and, being quite familiar with the United Church’s longstanding practice of trying to be all things to all people (a thing seeded in its very inception), I was a bit worried there would be nothing familiar when I walked in the door.

And yet, when I walked in, there was familiar carpeting, and familiar dark woodwork, and a familiar smell of lemon and beeswax. The entry was busy with ushers, just as I remembered from childhood, and someone immediately handed me a printed copy of the Order of Service, which I was very pleased to take. Stepping into the sanctuary—a wonderful space, bright with carved woodwork and stained glass, the walls painted yellow and blue, the arches hung with Arts-and-Crafts-inspired banners—was like returning to a familiar and beloved home. I found an empty pew not far from the back, hung my umbrella, shrugged off my coat, and sat, just as I had done so many hundreds of times before. The organ—a pipe organ, it seems!—pealed the opening chords of ‘O Come, O Come Emmanuel,’ and as voices raised to sing the processional hymn, I stood there, choking out the familiar words, crying with longing and relief.

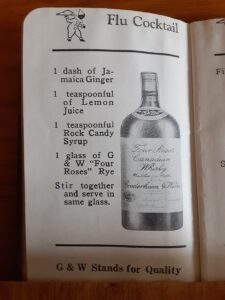

My first service in more than thirty years featured a baptism in which a delightful baby (who kept waving his arms as if to smite the minister) was welcomed into the family of the church. By this point I was no longer shedding tears, in part because the pre-Communion hymn, ‘O Jesus, Joy of Loving Hearts,’ included the ridiculous lines “We taste thee, O thou living bread, / and long to feast upon thee still,” which absolutely made me giggle—because the book in my purse happened to be Bill Schutt’s Cannibalism: A Perfectly Natural History (2017). Schutt’s book, of course, includes a chapter on Holy Communion, exploring the sometimes unholy history of the Eucharist and the, er, thorny theological issue of whether or not the sacramental bread and wine are meant to be consumed, literally, as the body and blood of Christ. Un/fortunately, I didn’t get a chance to partake in Communion—a ritual I had stopped participating in by the early nineties because, at the time, I could not square the Protestant principles of faith with any suggestion of literal Transubstantiation, and the Anglican service at which I last sat through Communion kind of hedged on the issue—because there was no pre-wrapped packet of Wine and Bread at my particular pew. Over the years I have grown satisfied that Communion, at least in mainstream Protestant churches, is understood to be a metaphor—Corinthians, at least as I have read it, makes it pretty clear that Communion is meant to be taken in remembrance of Christ, not as a sampler plate—so maybe next time I will partake.

The sermon was short, the choir lovely, the prayers familiar. A few things have changed–the Apostle’s Creed is a little different from the one I grew up with, and the hymnbook—Voices United—seems to have most of the familiar hymns, but in a completely different order. I didn’t think to note the version of the Bible the United Church now uses, but will probably bring my old copy of the King James anyway, as, for the most part, I prefer the poetry in its passages. I did note that, during the service, the Old Testament was called the Hebrew Bible, which seemed interesting and, really, preferable, considering that both Testaments are living texts.

After the service there was a fellowship hour, which sounded lovely although I did not attend as, frankly, I felt a bit overwhelmed and wanted to be alone with my thoughts on the rainy walk home. I’ll do so next time, because I think Runnymede may be my new church, and I’d like to start getting to know its community.