It’s November, and the air is velvety soft. Misty evenings precede gentle mornings, each more beautiful than the one before. At night the moon rides high in the trees, and all day the leaves, unusually beautiful this fall, detach themselves, one at a time, and drift down to rustle in the gutters.

It is a fall right out of Gray’s Elegy, and every front garden—still decorated for Hallowe’en, no one quite ready to break the spell—has the quality of a country churchyard. Stones askew in the tangled grass; leaves and lichen adorning gnarled roots and twisted branches like memento mori. November is a melancholy month, bringing with it the season of perpetual twilight. And yet: the light, so low on the horizon, illuminates the undersides of things.

Yesterday I rode downtown in the exquisite air to attend the Toronto Antiquarian Book Fair. I left early, because I wanted to visit some friends at the Art Gallery of Ontario; namely, the paintings and sculptures in the Thomson Collection. I’ve recently gotten an AGO membership, part of making good on a first-year-of-retirement goal of focusing on inclination and not only necessity, and it’s my intention to visit the Gallery (and not only the Thomson Collection) as often as possible.

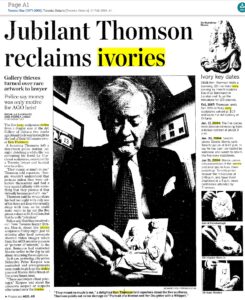

I do have a soft spot for the Thomson works, however. Ken Thomson was my first employer when, as a teen, I wrote for the Oshawa Times. And I felt another kind of affinity when, in 2004, five small ivory figures, on loan from the Thomson Collection, were stolen from the AGO. After their recovery several weeks later, Thomson clutched the ivories to his chest and told reporters he would sleep that night with the sculptures laid out in his bed. “They mean so much to me,” he said; adding, “people wouldn’t understand that perhaps unless they were collectors themselves and had a very special affinity with something that they possess that virtually became part of them.”

I am not, of course, a collector of ivories. But I have strong attachments to resonant objects, places, times and loved ones both living and dead. My grandfather’s portable Underwood typewriter, a gift years ago from my mother, which sits beside some of my father’s favourite books in a bookcase in our home library. My collection of hag stones, found mainly in gravel bars along Duffin’s Creek. And books, of course.

Recently we acquired, via curbside score, a lovely old glass-doored china cabinet that now houses my collection of antiquarian domestic manuals; guides to deportment and etiquette; books on gender and sexuality; interior design, architecture, landscape and gardening; and old cookbooks. I’ve been collecting these kinds of books since first buying a copy of Woman: Maiden, Wife, and Mother (1898) at a yard sale for a dollar in 1997—a remarkable, proto-feminist book that advocates for women’s full partnership in society even in the late Victorian era. I love what these volumes reveal about the culture and norms of their era, for good as well as ill. [I love all kinds of quirky old books, having volumes on phrenology, and patent medicine, and … oh: just all kinds of weird topics, but will write about these another time.]

Every day or so I open the doors of my new-to-me cabinet and visit my old books, breathing in their distinctive smell of cellulose and smoke (more here about the fascinating science of historic odours) tracing the gilt on their spines, and browsing their instructions, say, on invalid cookery or Accompanying a Lady to the Theatre. Each book contains a story, made up not only of the material within its covers but also of the story of the book’s history as an object. I have always been interested in marginalia, and inscriptions and bookplates, and laid-in papers, and notes scribbled in the end-papers (recipes, calculations, reviews, reminders). I am also interested in how books have traveled over time, including how they have come to the place—a book sale, and yard sale, a box of books set out at the curb—where I first encountered them. Some of my oldest books have journeyed across the ocean in steamer trunks, while others have remained in the same city, passed down through inheritance until, at some point, being discarded or sold. Each one is a treasure, and I am well aware of being only a custodian along their journey.

This has been my first year attending the Toronto Antiquarian Book Fair and, after two years of bookish events being affected by pandemic-related shutdowns, it has been a particularly good fall for book, publishing and literary events. The Fair felt like a homecoming event for antiquarian book aficionados, many of whom clearly knew one another. I am not entirely sure I belonged there: I am not a large volume (nor large budget) buyer of books, and my collecting is undisciplined and sometimes haphazard. I just like books. But I did chat with The Monkey’s Paw proprietor Stephen Fowler, and was pleased to make the acquaintance of the owners of The Scribe Bookstore, a new (since 2021) antiquarian bookshop located in Toronto’s east end. I also visited with booksellers I have bought from over the years, including Attic Books (of London ON) and Contact Editions (which seems to have sold much of its stock to Karol Krysik books, operating out of the same location, but running a separate booth at the Book Fair this weekend). Two booksellers I would have loved to see were Steven Temple of Steven Temple Books, formerly of Queen Street in Toronto (now based in Welland), and the late, lovely Nelson Ball, poet and bookseller.

I bought a few treasures at the Fair, including the following:

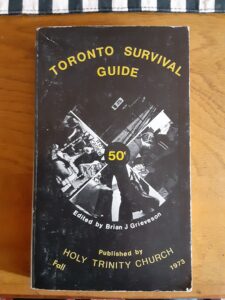

Toronto Survival Guide (Holy Trinity Church, 1973), a remarkable—and apparently now very scarce—guide to low-budget living in seventies-era Toronto. Edited by Brian Grieveson, of Rochdale College  fame (and author of the memoir Rochdale College: Myth and Reality; 1991) and publisher of Charasee Press (and introduced by none other than then-“tiny, perfect mayor” David Crombie!), the book is geared toward hippies, Draft Dodgers and folks ‘Goin’ Down the Road.’ Its practical chapters, on topics including Accommodation, Food, Legal Rights, Education, Recreation and Transportation, provide a vivid picture of the city’s counter-cultural interests in this era. The book includes medical advice for drug dealing with drug overdoses, STDs and pregnancies; information for gay Torontonians; a discussion of labour rights; a list of entertainment establishments; a guide to local bookstores that even, in the book’s fine print, fills more than a page; random insertions of Grieveson’s poetry, and illustrated instructions for making furniture out of salvaged material. It’s really a remarkable book, one I’d heard about but never seen. I’m totally hepped to add this to my library. [P.S. Apparently—according to a 1973 issue of University of Toronto student newspaper The Varsity—the Carling-O’Keefe Brewery had planned to sponsor the book, and paid some costs, but eventually backed out on the grounds that the book’s content was aimed mainly at “transients under 30.” Holy Trinity Church covered remaining costs and absorbed the loss—perhaps one reason why the book is so scarce now.]

fame (and author of the memoir Rochdale College: Myth and Reality; 1991) and publisher of Charasee Press (and introduced by none other than then-“tiny, perfect mayor” David Crombie!), the book is geared toward hippies, Draft Dodgers and folks ‘Goin’ Down the Road.’ Its practical chapters, on topics including Accommodation, Food, Legal Rights, Education, Recreation and Transportation, provide a vivid picture of the city’s counter-cultural interests in this era. The book includes medical advice for drug dealing with drug overdoses, STDs and pregnancies; information for gay Torontonians; a discussion of labour rights; a list of entertainment establishments; a guide to local bookstores that even, in the book’s fine print, fills more than a page; random insertions of Grieveson’s poetry, and illustrated instructions for making furniture out of salvaged material. It’s really a remarkable book, one I’d heard about but never seen. I’m totally hepped to add this to my library. [P.S. Apparently—according to a 1973 issue of University of Toronto student newspaper The Varsity—the Carling-O’Keefe Brewery had planned to sponsor the book, and paid some costs, but eventually backed out on the grounds that the book’s content was aimed mainly at “transients under 30.” Holy Trinity Church covered remaining costs and absorbed the loss—perhaps one reason why the book is so scarce now.]

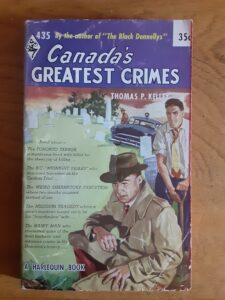

Canada’s Greatest Crimes (Harlequin, 1958). Written by noted Canadian pulp writer Thomas P. Kelley (of The Black Donnelleys fame), this book includes lurid accounts of crimes, the facts “a matter  of record,” the descriptions reportedly “accurate in every detail.” This may (or may not) be so, but Kelley certainly went for the sensational, writing in the introduction that the chapters “present the cream of bizarre crimes” and “reveal stories of murder and of mass murder; cases of diabolical cunning and unbridled sex, so fantastic as to seem incredible.” Fitting, one supposes, given that Harlequins, like other pulps of their era, were sold in newsstands, drugstores and bus stations to travelers looking for light (and often lurid) reads. The chapter titles are evocative: “While Satan Smiled,” “The Corpse Went Wandering,” and “Wild Women and Dr. Buchanan.” I myself was not immune to Kelley’s sensationalized approach: I bought the book because one of the stories, “The Toronto Terror,” sounded too exciting to leave behind. I’ve only begun reading, but if the pathetic fallacy that forebodes so heavily in the chapter’s introduction—

of record,” the descriptions reportedly “accurate in every detail.” This may (or may not) be so, but Kelley certainly went for the sensational, writing in the introduction that the chapters “present the cream of bizarre crimes” and “reveal stories of murder and of mass murder; cases of diabolical cunning and unbridled sex, so fantastic as to seem incredible.” Fitting, one supposes, given that Harlequins, like other pulps of their era, were sold in newsstands, drugstores and bus stations to travelers looking for light (and often lurid) reads. The chapter titles are evocative: “While Satan Smiled,” “The Corpse Went Wandering,” and “Wild Women and Dr. Buchanan.” I myself was not immune to Kelley’s sensationalized approach: I bought the book because one of the stories, “The Toronto Terror,” sounded too exciting to leave behind. I’ve only begun reading, but if the pathetic fallacy that forebodes so heavily in the chapter’s introduction—

On a raging fall night, over a hundred years ago, a flash of lightning split a Canadian sky and lanced downward to illuminate a small cabin in Northern Ontario, as well as the fields and thickly wooded area around it.

—is any indication, I’m up for a roller-coaster ride.

I have an enduring love for twentieth century interior design books, from the Edwardian period through to the 1950s or so (or, if I am honest, right up until the kitschiest and most hideous 1970s).  How to Decorate and Light Your Home (Coward-McCann, 1955) is, as its title suggests, a double-header of a book. It is also a bit of a Trojan Horse, having been co-written by an engineer with the General Electric Company, then in the midst of the Live Better Electrically advertising campaign it ran in concert with Westinghouse. Reportedly one of the most effective mass marketing campaigns of its era, Live Better Electrically spurred homeowners to purchase and install electrical appliances in hopes of winning recognition as a Medallion Home.

How to Decorate and Light Your Home (Coward-McCann, 1955) is, as its title suggests, a double-header of a book. It is also a bit of a Trojan Horse, having been co-written by an engineer with the General Electric Company, then in the midst of the Live Better Electrically advertising campaign it ran in concert with Westinghouse. Reportedly one of the most effective mass marketing campaigns of its era, Live Better Electrically spurred homeowners to purchase and install electrical appliances in hopes of winning recognition as a Medallion Home.

Recently at a yard sale I happened to buy a copy of The Electric Cook Book (1960), presumably produced as part of the same campaign, which similarly extolls the virtues of electrical appliances. The cookbook is emblazoned with the Live Better Electrically slogan and logo and makes explicit the view that electric living is “gracious living.”

The Live Better Electrically campaign may seem ridiculous six decades after its heyday, but in 2022 homeowners are being urged to landfill natural gas powered appliances, particularly stoves, and switch to electrical heating, on the grounds that natural gas appliances contribute more carbon gases and emit noxious fumes (e.g., nitrogen oxide and carbon monoxide) than their electric counterparts. Perhaps the ongoing campaign, delivered in the hectoring, moralistic language of far too much contemporary environmental activism (before the shouting begins let me say I note this with dismay as a person very deeply committed to environmental preservation, and as a person, incidentally, who line-dries all her laundry, but who cannot quite see the environmental merit in tossing her four year-old gas stove), would have more success if it took a page or two from the Living Better Electrically campaign of yore.

The Live Better Electrically campaign may seem ridiculous six decades after its heyday, but in 2022 homeowners are being urged to landfill natural gas powered appliances, particularly stoves, and switch to electrical heating, on the grounds that natural gas appliances contribute more carbon gases and emit noxious fumes (e.g., nitrogen oxide and carbon monoxide) than their electric counterparts. Perhaps the ongoing campaign, delivered in the hectoring, moralistic language of far too much contemporary environmental activism (before the shouting begins let me say I note this with dismay as a person very deeply committed to environmental preservation, and as a person, incidentally, who line-dries all her laundry, but who cannot quite see the environmental merit in tossing her four year-old gas stove), would have more success if it took a page or two from the Living Better Electrically campaign of yore.

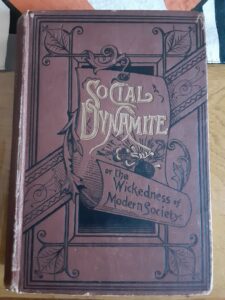

My final treasure from the Toronto Antiquarian Book Fair was Social Dynamite; or, The Wickedness of Modern Society, an 1888 book compiled from the discourses of T. DeWitt Talmage, an American  preacher, orator and supposed social reformer. Speaking of hectoring, Social Dynamite thunders at its readers against sin and social evil, with illustrations of “unfortunates” brought to ruin by licentious living. At the same time, it must be noted that the book also reads like a rather enthusiastic field guide to sin, with chapters like “Evil Companions” (this one includes the note, “No One Goes to Ruin Alone”–how comforting!), “Dark Deeds,” “The Babylonain Feast,” “High License, “Profanity, Drunkenness and The Social Evil” (I hastened to look up The Social Evil in this veritable encyclopaedia of sin, but, sadly, remain unclear whether he means drunkenness, prostitution, self-abuse, sodomy or all the above — but it seems Brooklyn was the place to go, with its streets “now night by night rivaling upper Broadway in its flambouyant wickedness.”), “Immoral Literature,” “The Theatre.” No evil is overlooked–not even Mormonism, Dancing or “Society Women.”

preacher, orator and supposed social reformer. Speaking of hectoring, Social Dynamite thunders at its readers against sin and social evil, with illustrations of “unfortunates” brought to ruin by licentious living. At the same time, it must be noted that the book also reads like a rather enthusiastic field guide to sin, with chapters like “Evil Companions” (this one includes the note, “No One Goes to Ruin Alone”–how comforting!), “Dark Deeds,” “The Babylonain Feast,” “High License, “Profanity, Drunkenness and The Social Evil” (I hastened to look up The Social Evil in this veritable encyclopaedia of sin, but, sadly, remain unclear whether he means drunkenness, prostitution, self-abuse, sodomy or all the above — but it seems Brooklyn was the place to go, with its streets “now night by night rivaling upper Broadway in its flambouyant wickedness.”), “Immoral Literature,” “The Theatre.” No evil is overlooked–not even Mormonism, Dancing or “Society Women.”

I love these old moralizing books, seemingly unvarying in their overuse of colourful description that must have made the sins their authors warned of seem thrillingly alluring to late Victorian readers.

Social Dynamite has already found a home in my cabinet of old books, and the other treasures will shortly be shelved with their kin.