Yesterday morning, bright and early, I took the streetcar halfway across town to attend the Old Book and Paper Show, hosted at the Artscape Wychwood Barns on Christie at St. Clair. The show was scheduled to open at ten, but when I walked in shortly thereafter, the hall was already buzzing with eager browsers and the booths were packed with people and an incredible range of wonderful paper-related things.

This was another first-time event for me. I’ve had a very serendipitous life discovering interesting old books and sometimes other paper treasures at book sales, yard sales, and in random boxes discarded at curbside. I’ve always maintained a large library at home, made up of books kept for research, teaching or pleasure reading, but suppose I have not really considered myself a Collector of books or paper ephemera. Although there are the 1940s issues of Chatelaine Magazine I snap up whenever they appear; and the nineteenth and twentieth century promotional cookbooks and kitchen-related pamphlets; and vintage books on animal husbandry, hunting and trapping, interior decor; and …

So maybe I have become a Collector after all.

At the Old Book and Paper show, I browsed the booths counter-clockwise, and was fortunate to arrive almost immediately at the delightfully-named The Book Not Mad, whose proprietor had laid out a very good selection of Canadiana, garden books, tame and therefore rather sweet erotica, and—catnip for me—old cookbooks and food-related promotional pamphlets. I rifled through those, and—with an eye on the clearly inadequate amount of cash I’d brought—bought three books.

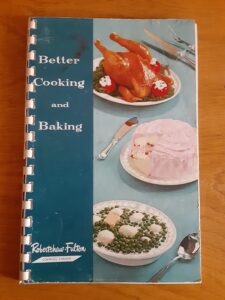

The first, Better Cooking and Baking, was published by Robertshaw-Fulton Controls Canada in 1956. I had never heard of Robertshaw-Fulton before, but have learned that the company produced thermostats and other controls for electric heating elements. Many of the recipes—for apple pie, mushroom casserole, tomato soup cake (yes: it sounds awful, but midcentury cookbook enthusiast and TikTok recipe tester B. Dylan Hollis says it’s not half bad with the right frosting)—are familiar fare in mid-century cookbooks. Where Better Cooking and Baking differs, however, is in that the recipes are divided into two principal sections: Oven Cooking, and Range Top Recipes. Along the way, readers—who may be new to electric cooking—are also instructed in Correct Placement of Pans in Oven and shown schematic illustrations of stovetop sensing elements for stovetop burners. The cookbook has delightful photographs, which include lovely now-vintage oven and serving ware, and includes very helpful guides to kneading bread, shaping rolls and preparing pastry. I am guessing this cookbook was given away at trade shows and possibly also came free with the purchase of electric ranges containing Robertshaw-Fulton controls.

The first, Better Cooking and Baking, was published by Robertshaw-Fulton Controls Canada in 1956. I had never heard of Robertshaw-Fulton before, but have learned that the company produced thermostats and other controls for electric heating elements. Many of the recipes—for apple pie, mushroom casserole, tomato soup cake (yes: it sounds awful, but midcentury cookbook enthusiast and TikTok recipe tester B. Dylan Hollis says it’s not half bad with the right frosting)—are familiar fare in mid-century cookbooks. Where Better Cooking and Baking differs, however, is in that the recipes are divided into two principal sections: Oven Cooking, and Range Top Recipes. Along the way, readers—who may be new to electric cooking—are also instructed in Correct Placement of Pans in Oven and shown schematic illustrations of stovetop sensing elements for stovetop burners. The cookbook has delightful photographs, which include lovely now-vintage oven and serving ware, and includes very helpful guides to kneading bread, shaping rolls and preparing pastry. I am guessing this cookbook was given away at trade shows and possibly also came free with the purchase of electric ranges containing Robertshaw-Fulton controls.

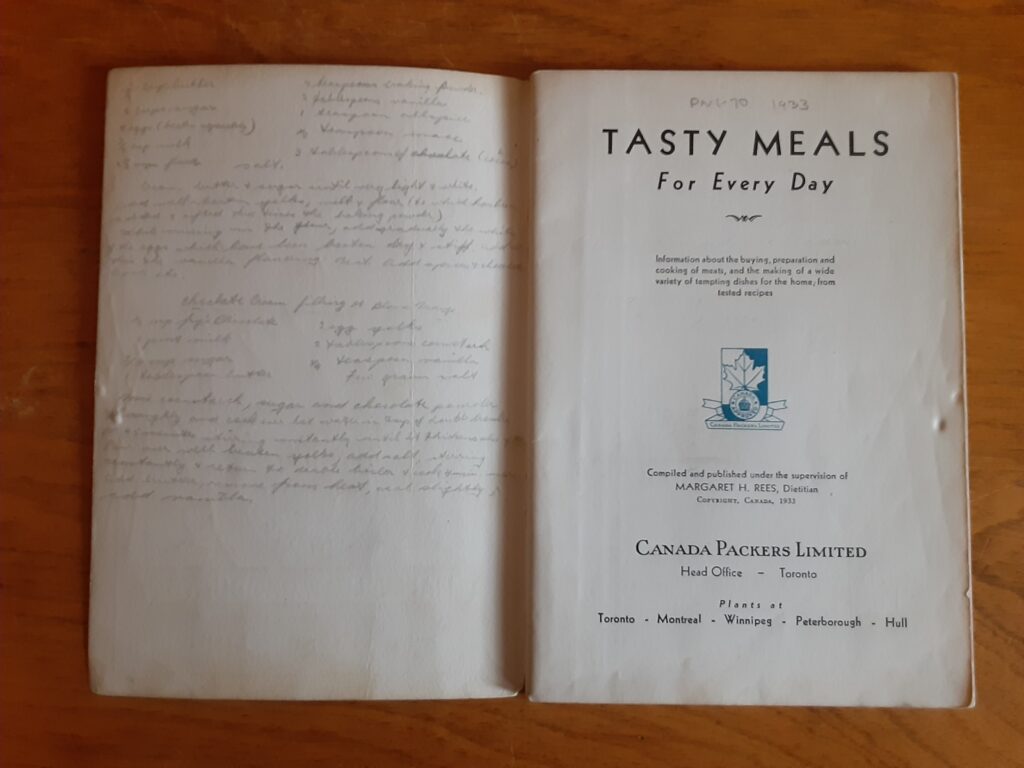

My second purchase from The Book Not Mad was Tasty Meals for Every Day, issued by Canada Packers under the Maple Leaf Products banner in 1933. By 1933 the Depression was well advanced, and many of the recipes in Tasty Meals for Every Day are geared toward “economical meals.” There are, for example, plenty of recipes calling for chopped or ground meats, and many of them involve meat cooked in and with vegetables in order to stretch a dish to feed an entire family. The recipes are credited to “Margaret H. Rees, Dietician” who, according to Elizabeth Driver’s Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (2008: 756), worked for Canada Packers and created or compiled recipes for at least one other company cookbook. I am guessing that this promotional cookbook was given away at public events like the Canadian National Exhibition.

My second purchase from The Book Not Mad was Tasty Meals for Every Day, issued by Canada Packers under the Maple Leaf Products banner in 1933. By 1933 the Depression was well advanced, and many of the recipes in Tasty Meals for Every Day are geared toward “economical meals.” There are, for example, plenty of recipes calling for chopped or ground meats, and many of them involve meat cooked in and with vegetables in order to stretch a dish to feed an entire family. The recipes are credited to “Margaret H. Rees, Dietician” who, according to Elizabeth Driver’s Culinary Landmarks: A Bibliography of Canadian Cookbooks, 1825-1949 (2008: 756), worked for Canada Packers and created or compiled recipes for at least one other company cookbook. I am guessing that this promotional cookbook was given away at public events like the Canadian National Exhibition.

I bought this cookbook for two reasons. First, Canada Packers operated out of the Junction-area Union Stockyards (at Keele and St. Clair) until 1983. The Stockyards—located less than a kilometre from my house, albeit on the other side of the proverbial tracks—has been developed into housing and large format retail spaces since the 1990s, although at least one slaughterhouse remains in operation, for now. The second reason I bought Tasty Meals for Every Day was because it includes handwritten recipes on the endpapers—my very favourite thing to find in an old cookbook. The recipes in my copy are an (unlabeled) chocolate cake recipe, which includes allspice and mace; ‘Chocolate Cream Filling or Blanc Mange;’ ‘Boiled Icing,’ Chocolate Frosting,’ and ‘Divinity Fudge.’ From these handwritten recipes, and from the grease marks in the cakes and pastries section of the cookbook, it seems pretty clear that the woman who received this cookbook kept it not for the meat recipes but for the desserts.

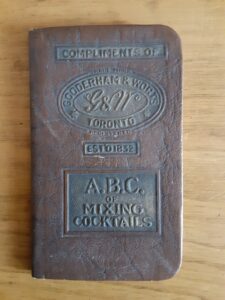

My third find at The Book Not Mad’s booth was this intriguing, vest pocked-sized A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails. The book is undated but was produced before 1932 and possibly prior to 1926, when the company (sold to industrialist Harry C. Hatch in 1923) was renamed Hiram Walker-Gooderham Worts in a merger (note: the Distillery District’s Distillery Heritage website lists the date as “circa 1928”). Toronto-based Gooderham & Worts Distillers was located in what is now known as the historic Distillery District: after production shut down in 1990, the site (named a National Historic Site in 1988) remained largely vacant until it was redeveloped into galleries, shops and condos that have maintained most of the site’s nineteenth century industrial architecture.

My third find at The Book Not Mad’s booth was this intriguing, vest pocked-sized A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails. The book is undated but was produced before 1932 and possibly prior to 1926, when the company (sold to industrialist Harry C. Hatch in 1923) was renamed Hiram Walker-Gooderham Worts in a merger (note: the Distillery District’s Distillery Heritage website lists the date as “circa 1928”). Toronto-based Gooderham & Worts Distillers was located in what is now known as the historic Distillery District: after production shut down in 1990, the site (named a National Historic Site in 1988) remained largely vacant until it was redeveloped into galleries, shops and condos that have maintained most of the site’s nineteenth century industrial architecture.

I’m not quite sure what to make of this little book. Prohibition wasn’t formally repealed in Ontario until 1927, and remained in effect in the US until 1933. In Quebec, however, Prohibition lasted only until 1921, and G&W (or HWGW, as the company became known) exported enthusiastically to the province. I have seen reference to a bilingual, 1930 edition of A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails, which obviously would have been distributed in la Belle Province (a digitized copy can be viewed here), so I am guessing that my edition (which includes a couple of mixed drinks with French names) would also have been made available in regions to which G&W could legally have exported alcohol. At the same time, the names of many of the mixed drinks—American Beauty, Astoria Cocktail, Bronx Cocktail, Manhattan Cocktail, Millionaire Cocktail, New Orleans Gin Fizz, Saratoga Cocktail, etc.—seem very American, very Jazz Age, meaning the book might have been subtly marketed to bootleggers’ American customers … or at least to Canadian drinkers who wanted to feel like they were consuming illicit beverages in a Detroit speakeasy.

In America Walks into a Bar: A Spirited History of Taverns and Saloons, Speakeasies and Grog Shops (Oxford University Press, 2011), my favourite historian, Christine Sismondo, writes of the relationship between Canadian distillers and American drinkers during Prohibition in the US,

Prohibition was effectively a farce in Canada. The country had no equivalent to the Webb-Kenyon Act, which had prohibited the shipment of alcohol from wet to dry states. Several distillers, most notably the Seagram Company, under the control of entrepreneurial Samuel Bronfman, took immediate advantage of this legal oversight and began building a mail-order alcohol empire within Canada. When America went dry, Canadian suppliers such as Bronfman saw the potential for sales south of the border and began ramping up production, ignoring ethical concerns. As Harry Hatch, president of Hiram Walker [Hiram Walker-Gooderham Worts], put it, “The Volstead Act does not prevent us from exporting at all. It prevents somebody over there from importing. There is a difference.”

This means it was entirely possible, perhaps even likely, that A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails could have found its way into a few American vest pockets prior to 1933. Which makes one wonder: had Jay Gatsby been carrying one, would he have survived George Wilson’s bullet?

Fun Fact 1: A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails includes a recipe for “Flu Cocktail,” which seems very of its post-1918 Influenza Epidemic era. In case anyone wishes to try it in the Covid era, it calls for

Fun Fact 1: A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails includes a recipe for “Flu Cocktail,” which seems very of its post-1918 Influenza Epidemic era. In case anyone wishes to try it in the Covid era, it calls for

- 1 dash of Jamaica Ginger

- 1 teaspoonful of Lemon Juice

- 1 teaspoonful Rock Candy Syrup

- 1 glass of G & W “Four Roses” Rye

Stir together and serve in same glass

Fun Fact 2: I paid $15 for my copy of A.B.C. of Mixing Cocktails, and thought it a fair price, but see that the book is considered scarce, and the couple of copies available online are listed for over $400 CDN. Yikes. Well; I guess I’ll drink to that. If you don’t want to spend the money on a print version, you can read a digitized copy online here.

From another seller’s booth I bought this 1941 copy of Emergencies in War, prepared by the Canadian Red Cross Society. The booklet was produced during the Battle of Britain (1940) and Blitz (1940-1941), during which Nazi warplanes carpet-bombed civilian as well as strategic targets in efforts to force Britain to submit to German terms (the same approach Russia has used in its targeting of civilian populations in Ukraine in 2022). Emergencies in War assumes its Canadian civilian readers may well find themselves under direct attack, and seeks to prepare them accordingly, with advice on dealing with shock, bleeding, burns and other wounds. It includes chapters on Psychology of Emergencies — noting, “fear is an implement of war” — and Air Raid Precautions.

From another seller’s booth I bought this 1941 copy of Emergencies in War, prepared by the Canadian Red Cross Society. The booklet was produced during the Battle of Britain (1940) and Blitz (1940-1941), during which Nazi warplanes carpet-bombed civilian as well as strategic targets in efforts to force Britain to submit to German terms (the same approach Russia has used in its targeting of civilian populations in Ukraine in 2022). Emergencies in War assumes its Canadian civilian readers may well find themselves under direct attack, and seeks to prepare them accordingly, with advice on dealing with shock, bleeding, burns and other wounds. It includes chapters on Psychology of Emergencies — noting, “fear is an implement of war” — and Air Raid Precautions.

A very relevant example from the Psychology of Emergencies chapter is the reported use of noise to terrorize civilian populations:

Fear has played a large part in the progress of the present war to date. Hitler, realizing that fear is the most powerful and deep-rooted instinct in human nature, has repeatedly, and successfully, and without conscience, made use of it to achieve his conquests. For instance, note how he has made use of loud noises to produce fear. German dive-bombers have sirens placed on their wings, and German bombs have vanes which make them scream as they descend. The masses of civilian population in Poland, Holland, Belgium and France broke into frenzy in the face of dive-bombers roaring down at 600 miles an hour, with sirens wailing, bombs screeching and machine-guns blazing, and swarmed on to the highways, effectively blocking them to fast manoeuvering of allied armaments.

For this chapter alone, the book is excellent, and—it must be said—timely, more than eighty years later. This, incidentally, is a subject I will shortly have much more to say about over at The Space Between Us.

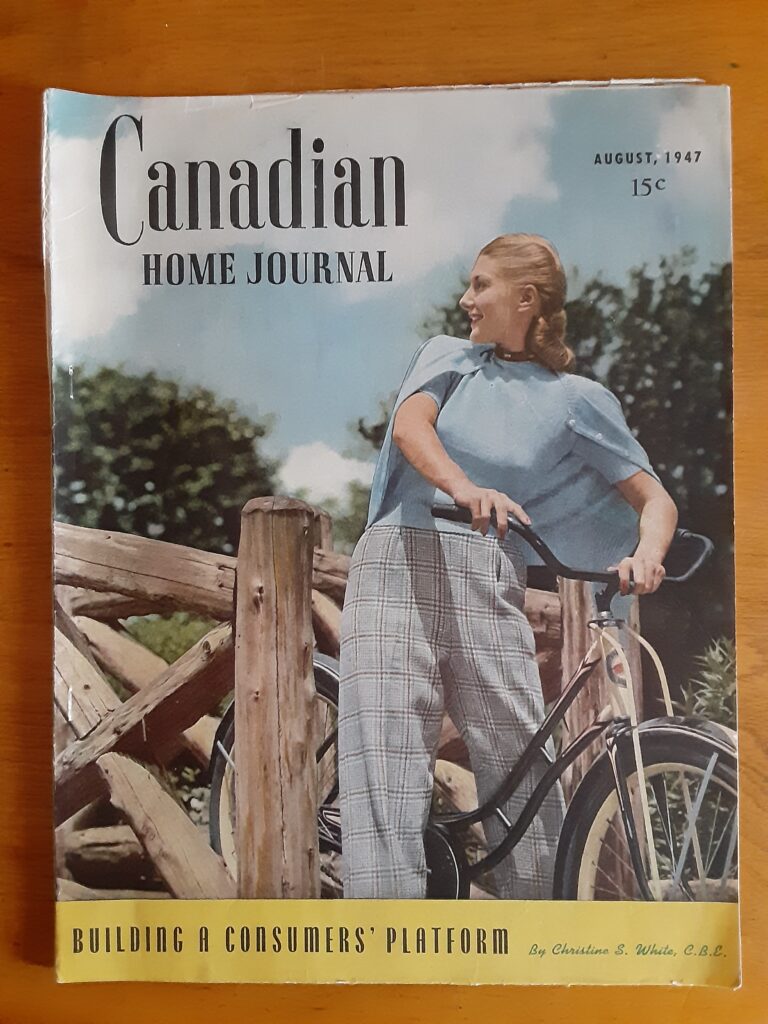

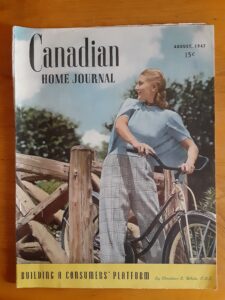

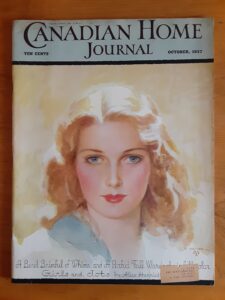

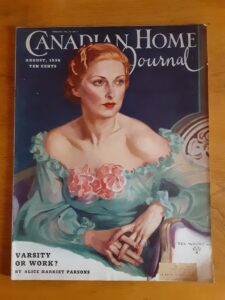

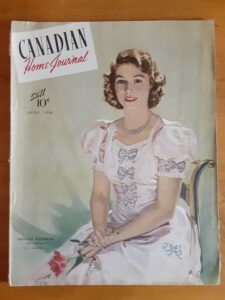

My favourite finds at the Old Book and Paper Show were 1930s and 1940s issues of Canadian Home Journal, a woman’s magazine that ran from 1905 as The Home Journal (and 1910 as Canadian Home Journal) until 1958. Middlebrow Canada describes the CHJ as similar to Chatelaine Magazine, but in browsing the issues I bought yesterday, I’d say the CHJ is notably lighter weight in terms of the issues it addressed. Where Chatelaine, even in the thirties but definitely by the forties, is usually proto-feminist in orientation, and tackles social issues intelligently and pretty much head-on, the CHJ takes a softer approach, foregrounding stories and serialized novellas in which traditional themes are advanced and including (at least in my reading so far) much briefer non-fiction articles that tackle their subjects somewhat in passing. Where CHJ has it over Chatelaine, however, is in its visuals, which are wonderful. Chatelaine covers are very good, but look at these CHJ covers! I just love them.

I hesitate to mention advertisements, because far too often ephemera resellers rip ads out of old magazines and sell them individually as tear sheets. I don’t get this at all. It seems to me that the ads lose their value when removed from their context, particularly the record the magazines, their format, design, articles and advertisements offer of the era in which they were published. Ads can be scanned, which I suppose would undercut much of their resale value. And yet—advertisements are emblematic of the mass production era, and maybe it would be better to enjoy them that way.

Still, have a gander at this gorgeous advertisement for Congoleum Gold Seal Rugs! Isn’t it incredible? I would die—positively die! (only metaphorically, of course)—to have this kitchen!

So endeth my day at the Old Books and Paper Show. There was so much I didn’t have a chance to enjoy, especially the numerous boxes of old photographs and postcards at various vendors’ tables. They were utterly swarmed with people and I didn’t want to push in. I was also, if I am honest, experiencing information overload. Also, the vendor from whom I bought the Canadian Home Journals had tons and tons of old magazines (including old Vogues) and catalogues (Eaton’s, Canadian Tire, etc.) I would have loved to look at longer. Maybe next time. It was a fun event, and I’ll definitely go to the next one.