Today is the second Sunday of Advent—the second Sunday of the Christian liturgical year, and also the second Sunday of my return to the fold after three decades’ absence from church—and it felt good, once again, to put on a nice dress, walk down to Runnymede United Church in the bleary December sunlight and sit in an already familiar pew in that beautiful sanctuary.

Celebration of the second Sunday of Advent revolves around the theme of Peace, and I was quite curious to see how the Runnymede service would address this theme amid intersecting global crises, perhaps most pointedly the devastation and peril resulting this year from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The readings—Isaiah 11:1-10 and Matthew 3:1-12, both traditional for the second Sunday of Advent—offer meditations that not only seem a bit incongruous amid the celebratory lead-up to Christmas, they advance complex, even paradoxical notions of peace. Isaiah promises the deliverance of God’s people, Israelites and Gentiles alike, alongside a veritable litany of peaceful outcomes: wolves lying down with lambs; calves with lions; wild creatures lead by a child; etc. etc.. But the text also calls for a leader or ensign who will “smite the earth with the rod of his mouth, and with the breath of his lips shall he slay the wicked.” The passages from Matthew promise salvation through baptism, but demand repentance. Both readings bristle with urgency, evoking barren, broken, battle-scarred landscapes (not only of the soul) that must be traversed before peaceful rivers can be reached and good rootstock (the defining metaphor in both passages) nurtured. The promise of peace—a renewed Covenant; the Kingdom of Heaven; the presence of a Savior—seems very real but distant, and difficult to secure.

As a member of Generation X, who grew up simply assuming we would all be bombed to annihilation in a nuclear Armageddon, and who then saw the tremendous promise of genuine peace brought by the end of the Cold War turned rapidly to ruin, simplistic invocations of ‘peace’ strike me as profoundly empty. The notion that one can just “say no to war”—as if aggressors will then simply go away and stop their genocides—seems to require an ignorance of reality that risks becoming complicit in the very evil it purports to oppose.

I am the only churchgoer in my household because my husband, an avowed if open-minded atheist, is also the son of someone who survived the Romanian Holocaust only because her mother sent her as a five year-old, by train with a near stranger, away from Czernowitz (now called Chernivtsi and, due to movement of the border, located in Ukraine) being ‘liquidated’ of its Jews, most of whom perished in Transnistria. It didn’t matter that my husband’s relatives were well-educated, secular, German-speaking engineers, doctors, lawyers and business people: they were still marked for genocide. And if the rescue of what remained of Europe’s Jews during the latter part of the Second World War was somewhat incidental to Allied efforts to stop Hitler’s conquest of Europe, it was nonetheless the result of a belated but real understanding that “peace for our time” will invariably fail if it remains willfully blind to murderous reality.

In this morning’s service the arduous, aching, perilous effort involved in any quest for peace was underscored by the choir’s simply superb performance of the haunting, powerful anthem “Dona Nobis Pacem,” “Dona Nobis Pacem”—or ‘grant us peace’—is, at its core, a simple, heartfelt plea, a short lyric from the Agnus Dei of the traditional Latin mass, sung as a round or spoken as a call and answer (which is how I have heard it in my church-going). The arrangement the choir sang so powerfully this morning was a somewhat recent one, prepared by contemporary American composer Z. Randall Stroope. If, like me, you have a prejudice against contemporary arrangements, Stroope’s setting will blow your mind. Seriously: have a listen here. It’s simply astonishing.

Stroope’s arrangement of “Dona Nobis Pacem” was a brilliant choice for this morning’s service because it appears (I say ‘appears’ because I am terrible at discerning lyrics without a printed text in front of me) to incorporate the words from Isaiah 11: 1-10, which was, of course, one of the readings for today’s service emphasizing both the promise of peace and the grave difficulty of achieving (let alone maintaining) it.

The city of Czernowitz / Chernivtsi, from which my mother-in-law’s family was deported in 1941, currently attracts refugees fleeing the Russian invasion in eastern Ukraine. Many of the refugees are children, five or six years old, like my mother-in-law was when her mother sent her away in hopes of ensuring her survival. Many of these refugees are headed in the same direction—south, into present-day Romania, because missile strikes interrupt even the provisional peace of a city so far spared the worst of the invasion.

In this morning’s service one of the ministers invited worshippers to consider the spaces and circumstances that bring them peace, and I thought about how often, in my experience and in human affairs more broadly, peace is provisional; how sometimes it reduces to a moment of remission in the furious face of disaster. I thought about how often peace must be fought for and defended with vigilance, like space or the right to exist. I thought about peace as a kind of mercy.

I also thought, as always, about my secret garden, where even in times of sorrow I commune with the bumblebees and witness the miracle of life unfolding in flowers and fruit. In this domain, which holds itself as much as possible beyond human affairs, peace is ingrained in the relationships between living organisms and in the flows of energy throughout the vibrant cosmos.

I also thought, as always, about my secret garden, where even in times of sorrow I commune with the bumblebees and witness the miracle of life unfolding in flowers and fruit. In this domain, which holds itself as much as possible beyond human affairs, peace is ingrained in the relationships between living organisms and in the flows of energy throughout the vibrant cosmos.

I find peace, too, in the wind that roars in the trees, and in solitary progress through the woods, and in moiling for fossils on gravel bars, and in a kayak gliding through lilies in an oxbow lake. In these moments there is no urgency; there is no crisis; there are no demands. There is only the movement of light and shadow, the slow motion of the earth; the voice of Creation saying: listen.

In moments of peace I pray for Ukraine.

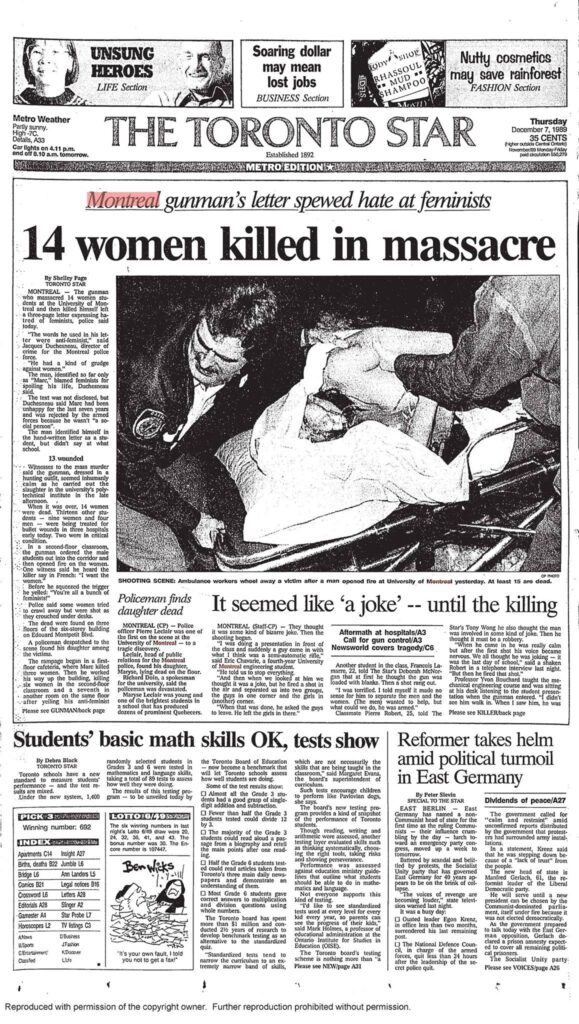

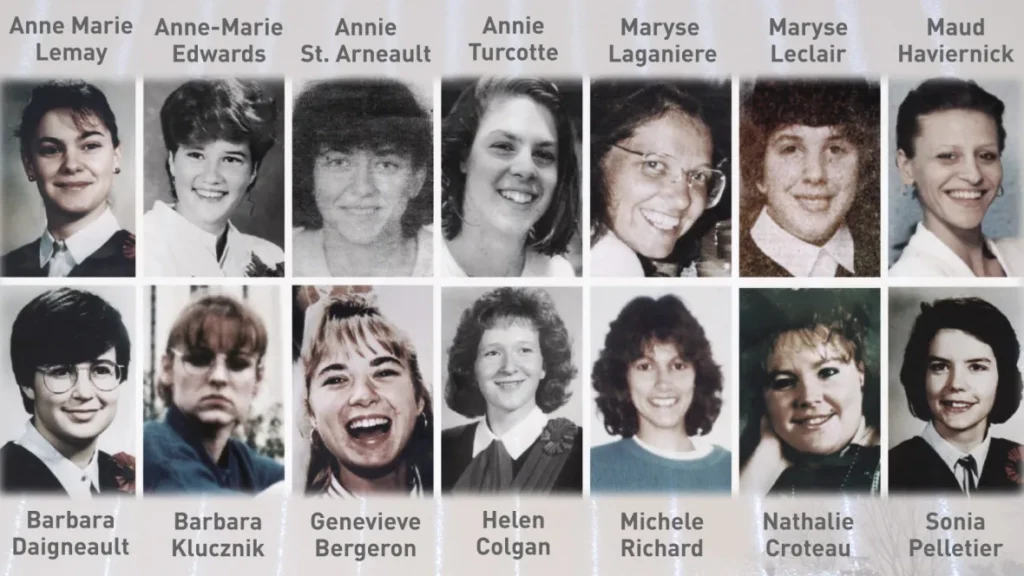

I don’t remember where I was on 6 December 1989. I do remember following the massacre on the news, and struggling to grasp its implications. At 17 my relationship with feminism was complicated; it is even more complicated now. But what struck me then, and strikes me even more strongly now, is that by “feminists” the shooter really meant “women.” That is what I remember, and that is what I think of 33 years later, in a year in which women’s lives and bodies and basic rights seem as much under threat as ever.

I don’t remember where I was on 6 December 1989. I do remember following the massacre on the news, and struggling to grasp its implications. At 17 my relationship with feminism was complicated; it is even more complicated now. But what struck me then, and strikes me even more strongly now, is that by “feminists” the shooter really meant “women.” That is what I remember, and that is what I think of 33 years later, in a year in which women’s lives and bodies and basic rights seem as much under threat as ever.