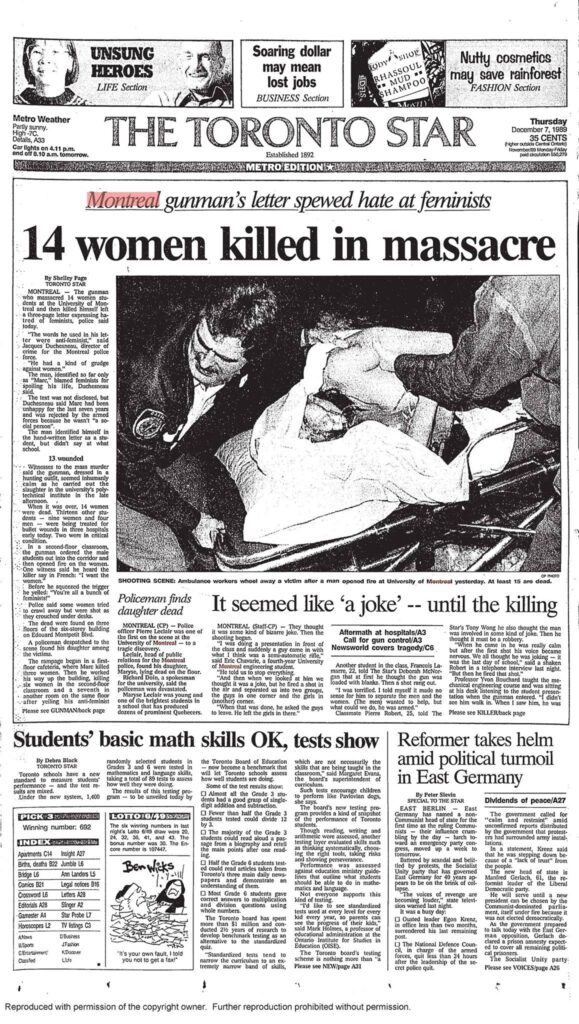

I don’t remember where I was on 6 December 1989. I do remember following the massacre on the news, and struggling to grasp its implications. At 17 my relationship with feminism was complicated; it is even more complicated now. But what struck me then, and strikes me even more strongly now, is that by “feminists” the shooter really meant “women.” That is what I remember, and that is what I think of 33 years later, in a year in which women’s lives and bodies and basic rights seem as much under threat as ever.

I don’t remember where I was on 6 December 1989. I do remember following the massacre on the news, and struggling to grasp its implications. At 17 my relationship with feminism was complicated; it is even more complicated now. But what struck me then, and strikes me even more strongly now, is that by “feminists” the shooter really meant “women.” That is what I remember, and that is what I think of 33 years later, in a year in which women’s lives and bodies and basic rights seem as much under threat as ever.

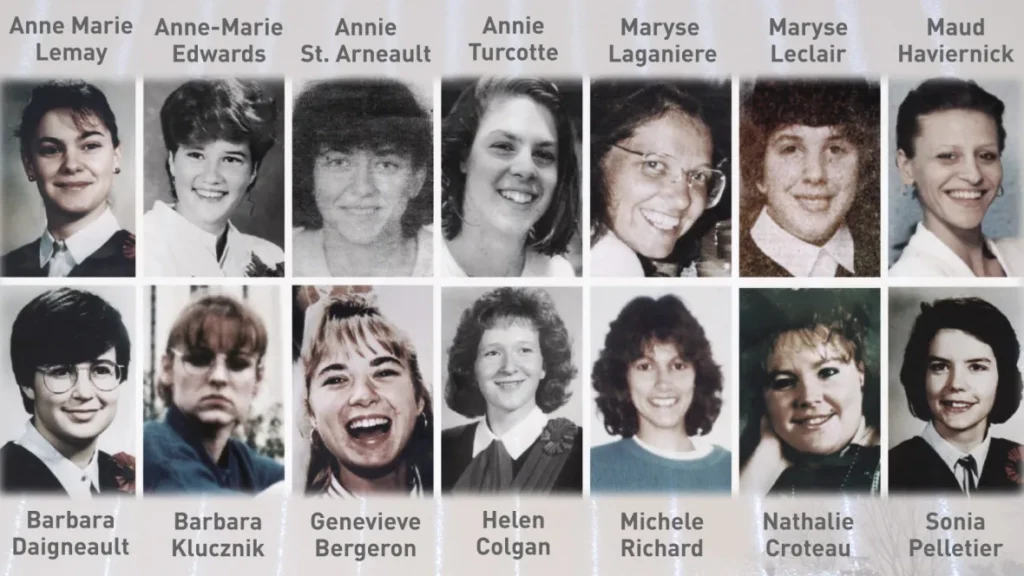

Twelve of the fourteen women murdered that day—Geneviève Bergeron, Hélène Colgan, Nathalie Croteau, Barbara Daigneault, Anne-Marie Edward, Maud Haviernick, Maryse Leclair, Anne-Marie Lemay, Sonia Pelletier, Michèle Richard, Annie St-Arneault, and Annie Turcotte—were engineering students. The thirteenth woman, Maryse Laganière, worked for the university. The fourteenth woman, Barbara Klucznik-Widajewicz, was a nursing student.

The women were young; the youngest twenty; the oldest 31. All were vibrant, accomplished, hard-working women, and as the years pass I find myself thinking, more and more, about what kinds of lives they would be living today. By now they would be in their fifties; two just past sixty; all likely at the peak of their careers; thinking about retirement, hoped-for grandchildren, ailing parents, new winter boots, vacation plans, the state of the planet. The kind of women one might encounter breezing into a smart café, shrugging the snow from their coats before sitting down to share gossip over lunch and a latte. Greying hair; a cancer scare; someone’s new love; variable rate mortgages; the fluctuating price of gas.

One of the women turns to another and asks if she has heard from Maryse lately, or Annie, or Helene, or Genevieve. A pause; a shaken head; a look of confusion. Oh; do you mean— I’m not sure; I don’t …

All at once the film recoils in its cylinder, stuttering briefly before rolling backward in a chaotic rewind. The projector shudders, lights flashing wildly; suddenly something rattles and pops and the whole thing derails. Metal shrieks, the reels rip loose from their casing, and in the background there is disembodied shouting. The film unspools into wild coils, frames snapping apart, stills spilling across the gritty floor.

Soon—but far too late for any hope of repair—all this tangle of metal and celluloid comes to rest, and in the profound, echoing silence punctuated by lights pulsing intermittently against the gloom, the only discernible images are those of the fourteen faces in an endless sequence of frames, eerily soundless and still.