Seeing Stones

On an old washstand in the bay window of our living room I keep a small shrine of stones we’ve found on local beaches and gravel bars. Some of the stones have faces. One of them contains a fossil that looks like a fish tail. One is a small section of lake-washed brick with the word ‘Toronto’ still visibly embossed on it. In a small bowl are weathered marbles we’ve found along Lake Ontario, and a perfectly rounded, egglike stone my mother once found in the roots of a very old oak tree. And some of the stones are stones with holes worn through them by wave action or other weathering processes. In European culture these are variously called ring stones, worry stones, eye stones, hagstones, witch stones, fairy stones, Odin stones, druids’ glass (Gloine nan Druidh), adder stones, serpents’ eggs, and Hühnergötter (“chicken gods,” which reportedly keep animals safe from injury and in mythology reference conflicts with the Slavic house spirit Kikimora). Recently I have seen them described as “seeing stones,” although the cultural etymology (attributed variously to Indigenous people, Tolkien’s Middle Earth, and Mormons) seems unclear. Despite uncertainty about the mythical origins of the term (and the possibility that it is simply borrowed, like so many other things, from Tolkien, an enthusiastic mythology borrower himself), I like “seeing stones” best, because one does quite literally see through them, and because their talismanic properties evoke so many other kinds of divination.

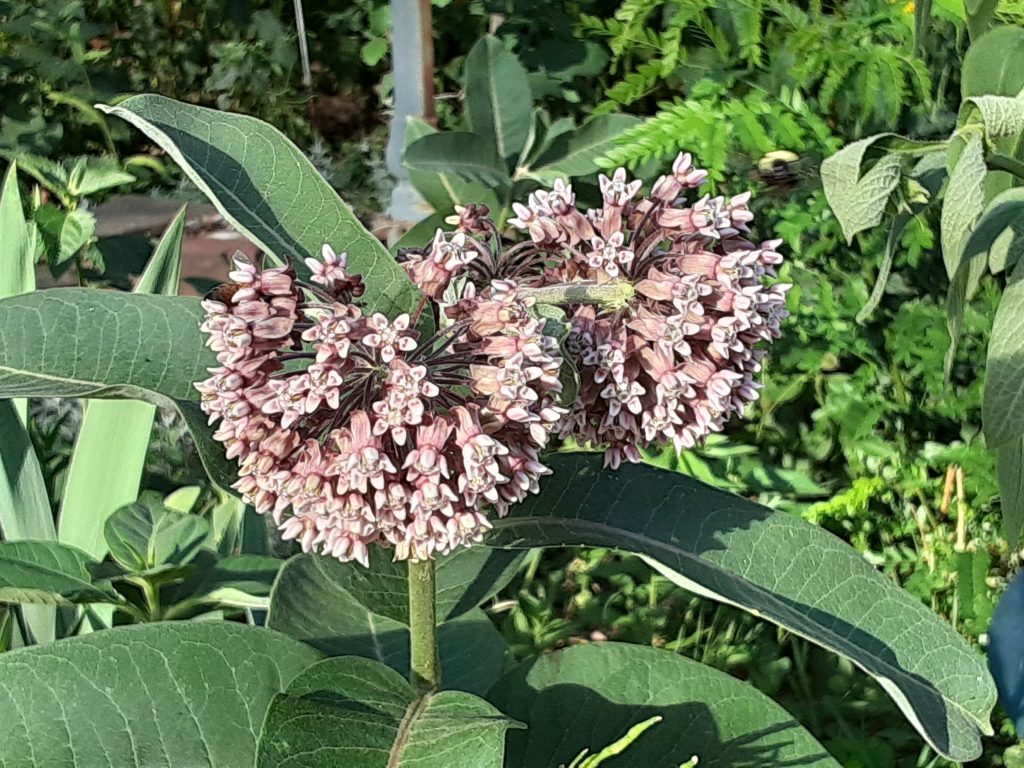

Apart from mythological claims about their origins (e.g., that they are formed from the secretions of serpents), seeing stones are the product of a variety of geological and biological processes. Reportedly in Europe seeing stones are commonly formed in flint nodules that weather out of sedimentary strata and wash down streams or tumble about in the ocean. Flint is itself a propitious material, having been used for toolmaking (e.g., flintknapping) by Stone Age cultures dating back at least two million years (the palaeolithic use of flint and application of geological knowledge to mine it is an enormously fascinating subject). Wave action or the grinding action of smaller stones gradually wears holes into and eventually through these stones, which may then be found on cobble beaches all along the sea (for an account of flint hagstones and their history, read stonemason and writer Alex Woodcook‘s wonderful essay “In the Eye of the Hagstone” in Elementum). Recently I learned about piddocks, which are small mollusks that carve burrows into limestone, leaving behind rounded holes and sometimes networks of tunnels in the soft sedimentary rock. Other mollusks and sea worms also reportedly burrow into stone, and sometimes their shells may be seen in these tunnels, rattling around like miniature memento mori.

In Ontario, flint (more commonly called chert) beds (and occasionally outcrops) can be found in Hudson Bay-area Precambrian shield and in the Paleozoic bedrock of the Great Lakes area. But in my experience, seeing stones form in fossil-rich limestone or dolostone that has been eroded out of the sedimentary bedrock or scraped loose by glaciers and then washed down rivers and streams toward the Great Lakes. Over thousands of years the stones are tumbled smooth, and the remains of Paleozoic fossils–formed out of marine creatures pressed into the bottom of a shallow sea underlying much of contemporary North America more than 360 million years ago–dissolve out of them, leaving holes and tunnels behind.

I have been collecting seeing stones since I was ten. In 1981 my parents bought an old bungalow on land perched above a deep, wide southern Ontario ravine with a creek flowing at the bottom of it and thereafter, for all the years we lived adjacent to Duffin’s Creek, I spent hundreds or perhaps thousands of hours walking in the stream bed, pouring over the gravel bars that formed and reformed along the inside stretches of the creek’s meandering curves. My mother did the same thing, and after she died I discovered an old Kool-Aid can in which she had saved the seeing stones she had found along the creek. Every time I have returned to Duffin’s Creek in the three decades since we moved away from the area, I have knelt down and searched until I found a seeing stone for each of us. I do the same thing when my daughter and I go beach glass hunting along Lake Ontario, including yesterday, when after a long ride downtown along Lakeshore Boulevard (wondrously closed to cars for ActiveTO), we ventured onto the pebble beach at Ontario Place, kicked off our sandals, and got down to the business of looking for interesting things along the water’s edge. We did not stop until we had found a seeing stone for each of us, and a third to take home to my husband. The stones along this particular beach look as if they had been brought there for erosion control, but almost certainly they came from a southern Ontario quarry formed in glacial till deposited during the Quaternary ice age, which in southern Ontario ended around 12,000 years ago. Already long since tumbled to rounded smoothness, their fossils scoured or dissolved out of them, these stones will continue to wear along the edge of Lake Ontario, their cups and tunnels widening and deepening until almost every stone will become a seeing stone.

In my early teens I read an essay called “The Talisman,” by Canadian journalist Greg Clark, which recounts the protective properties of seeing stones. As a young boy, Clark’s grandmother advises Clark that, should he ever find a stone with a hole in it, he should loop a string through it and wear it around his neck, because “[i]t will protect you from the arrow that flieth by day […] and the pestilence that walketh in darkness.” Years later, on leave from the battles of the First World War (in which Clark becomes a decorated veteran of Vimy Ridge), Clark finds himself sitting on the stony beach at Brighton, and glances down upon the gravel and stares “straight as a needle, into the eye of the hole in a little pebble.” Clark picks it up, and walks to a bathing hut where he obtains a length of fish line, and ties the stone around his neck, where Clark wears it for the remainder of his life, and reports that “in all the long years,” no flying arrow nor crawling pestilence has found him.

For many years I, too, wore a stone with a hole in it on a leather thong around my neck. That stone now sits with a collection of other special stones on the desk in my office, where I touch it often in order to divine all the things that may be seen through the eye of a seeing stone.