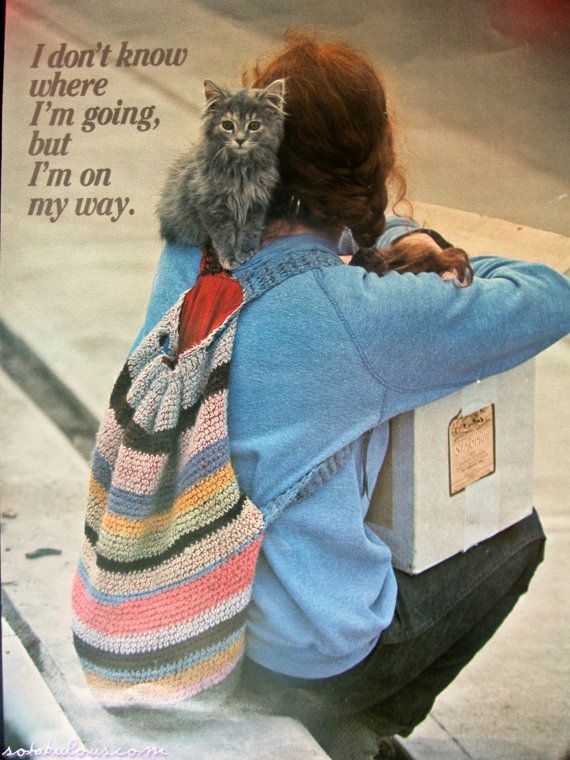

On the wall of my senior high school Calculus classroom was a poster of a girl sitting on a curb with her belongings and a cat. The accompanying text read, “I don’t know where I’m going, but I’m on my way.” I took Calculus in my final term of high school — why I am not sure, as around that time I was accepted into the undergraduate program in Geography at Queen’s, for which Calculus was not a requirement (although it did come in handy in a geomorphology course precisely once) — and, rather than focus on derivatives and asymptotes, spent much of the term looking up at that poster, which might as well have been a picture of me.

“I don’t know where I’m going, but I’m on my way” is the refrain of a once-popular World War I song composed by songwriter George Fairman (1881-1962). A very similar phrase had appeared earlier in Incidentals, a 1900/1904 volume of essays and aphorisms published by American writer Carl Sandburg (in Sandburg’s book, the line actually reads “I’m an idealist. I don’t know where I’m going but I’m on the way.” Interestingly, in 1999 or so Dionne Warwick recorded a song with Burt Bacharach (lyrics reportedly written by Hal David) called “On My Way,” which opens with “I don’t know where I’m going / But I’m on my way.” The repeated use of this phrase — including its attribution, variously, to Carl Sandburg and (probably erroneously but who knows?) to Carl Sagan, and its appearance on the poster hanging on the wall of my high school Calculus classroom — suggests it has enduring resonance (or alternatively, perhaps, that songwriters are as prone to borrowing as regular litigation over rights suggests they may be).

The poster and the phrase printed on it resonated strongly with me, and for years afterward I thought about it often. About fifteen years ago I began searching peripatetically online for the poster or even an image of it, without luck until a couple of years ago when I came across it listed in the holdings of the Oakland Museum of California. I now have a copy of the poster framed on my office wall, a constant companion and friend.

I was born on a Thursday, and always felt the old sing-song line “Thursday’s child has far to go” described me utterly.

I have always been preoccupied with location and spatiality. Always. My earliest memories are directly spatialized, and, well, I was always going to be a geographer, always was a geographer, long before I ever learned the word, or knew a geographer was a thing one could ‘be’ or geography a thing one could ‘do.’

For me geography has never been primarily about maps, or globes, or the memorized names of rivers or Gross Domestic Product of various countries. It seems to me that colouring in maps (the longstanding ritual of elementary school geography classes) is one of the least interesting ways to learn about place and space — although having kids create maps, including maps of the imagination, is a highly valuable and worthwhile activity. Place is an idea and an experience long before it is an encoded set of categories. The capacity to orient — in space, across time, toward the self and others, toward ideas, around representations and meanings of place — is in some ways ingrained but needs also to be cultivated, learned, developed, expanded, explored.

The pandemic has constrained spatial movement in many ways: travel is largely curtailed and many regions have undergone weeks- or months-long shutdowns geared toward limiting the spread of the Covid-19 virus and its variants. But it has also created compensating opportunities for people to practice more local forms of exploration. Biking, for example, has become so popular in many cities (including Toronto) that bike shops are sold out of stock and parts are back-ordered for months. Walking has also surged in popularity, and sidewalks, parks and hiking trails are busy with forest bathers, joggers making up for lost time at the gym, families out for strolls, and psychogeographers letting the landscape take them where it will.

When I was young we lived adjacent to a wide, deep southern Ontario ravine with an old meandering creek flowing along the bottom of it. In my teens I walked down into the ravine at least once or twice a week and then eventually almost daily, regardless of the weather, or season, or time of day. I did so in part because it was the only place I could be alone with my thoughts, and also because something in the ravine — particularly when the wind was high or the cold very still or when the spring peepers were trilling their secretive songs — pulled me down into it. Over the course of several years I came to know a mile-long stretch of it intimately: every bend of the creek and slope of the ravine, the shape of its oxbows, the ebb and flow of its gravel bars, the flotsam that accumulated in logjams, the habits of fish and heron, the way the trees swayed in windstorms, the smell of cedar thickets, the pressure of ice against the edges of the swamps. Over the decades I have returned to Duffins Creek semi-regularly, first with my father and then with my daughter and sometimes alone, and while the creek bed has shifted, trees have fallen and regrown, and although development and a paved recreational trail have altered the watershed and floodplain in some places, leaving other parts of the ravine to grow wilder than ever, I can still navigate the ravine nearly with my eyes closed.

In an era characterized by global movement (and often displacement), it is a privilege to be able to remain in a place long enough to get to know it intimately. People who live in a community but never walk its streets or visit its parks do not really come to inhabit a place, regardless how long they live there. In some ways my childhood and adolescence were very constrained, but access to Duffins Creek (the grammarian in me will always call it ‘Duffin’ or ‘Duffin’s’ Creek) was my passport not only to multisensory, fully embodied experiences of a particular place, but also to insights into the way landscapes function more generally. In high school I was fortunate to take a physical geography course with a superb teacher who took our class down to Duffin creek to measure its processes and flows. At the time it seemed a revelation to realize I already knew so many things about how the creek worked, and that our quantitative and qualitative observations (velocity across the profile of the stream bed, turbidity, what we would find in suspension in the water column, etc.) would line up so utterly with my embodied experiences of the creek. It is not an exaggeration to say that this field trip was life-changing for me. Perhaps above all it affirmed my sense that experiences matter, including embodied and even inchoate ones, and underscored my emerging views about the importance of paying attention to the connections between things that can be measured and the things that can only be sensed or felt. In short, this trip turned me into a confirmed phenomenologist. [It should also have turned me into a geomorphologist, but sadly did not, although as an undergraduate student I think I took every geomorphology course offered, and have taught physical geography courses on and off for years.]

After spending graduate school largely in transit between cities, houses and apartments, I was fortunate to move into the community where I still live, eighteen years later (and where my husband has lived for more than thirty years following a childhood of continental displacements). In the early years of our marriage, when our house still needed furnishing and when people still put amazing sorts of architectural salvage and other interesting things out to the curb, we would head out every garbage night, usually on foot or bike, to see what the neighbourhood had on offer. On these excursions we rarely went far, but found many things worth bringing home: beautiful old (and sometimes contemporary) furniture, elaborate old windows, sometimes with leaded panes or stained glass, thick wood planks of the sort now described as ‘barn board,’ a lovely 1920s bed frame that eventually became the centrepiece of our guest bedroom, a huge box filled with crystal goblets, a large, brand new Portmeirion Botanic Garden serving dish I still use for special occasions, a garden bench, planters, plant stands, tools, books. In a dumpster parked in front of a house being gutted to the studs I once found an old washboard and kitchen scale. We even co-wrote an essay about our garbage gleanings published in GreenTOpia: Towards a Sustainable Toronto (Coach House Books, 2007) and excerpted in a now-defunct local weekly.

The most important thing about our garbage excursions wasn’t the things we found, however. It was the opportunity to encounter our neighbourhood in all its moods, at all hours and in all seasons, and to move freely through all of them. Late one summer night we rode out, the moon floating high in the trees, a wind soughing in their branches, warm air on our skin, and in that instant I felt more alive than I have ever felt.

Early yesterday morning I went out walking with my like-minded neighbour, an artist who walks out nearly every morning but always makes sure to head out on garbage day. It was my first intentional garbage walk in years. We left just before sunup, while the waning Worm Moon still floated in the southern sky. We covered about four kilometres of terrain, although as the crow flies we were never more than about a kilometre from home. When we set off we did not have a specific plan, although we thought we might keep an eye out for architectural salvage and other bits and bobs worth hauling home. In the end we did not bring anything back other than a couple of books from free libraries (including, for me, a first edition of Matt Cohen’s Night Flights (Doubleday, 1978)), but we traversed every block in our immediate neighbourhood, considering objects set out at curbside, talking about our favourite houses (usually the ones with some mystery to them), and discussing what we know of their pasts, and exclaiming over the ‘coming soon’ sign posted in front of a long-abandoned house three blocks away, and considering whether chairs, planters and other objects were worth hauling home. The streets were quiet, so we jaywalked at whim, gawking at everything we wanted to see, and enjoyed our freedom of movement in a city largely shut down by the pandemic.

Last week, on my birthday, after many years as a cyclist and pedestrian, I obtained my G1 driver’s license, the first step toward becoming a licensed driver in Ontario. I actually know how to drive and am not bad at it, but have never completed all the steps to becoming fully licensed. We are planning quite a bit of travel after the pandemic is over, within Canada, to Israel, Europe (for me and our daughter) and possibly (for my husband) India, and this seems like a good time to obtain a license. In my experience driving attenuates the visceral experience of both movement and place, but it seems to me there will be compensations. Even with greater mobility, most of my trip plans are likely to remain local. There are quite a few country roads I’d like to drive, for example, and little towns I’d like to visit or revisit. There are rivers and lakes we plan to kayak and camp beside. There are a couple of abandoned farms I’d like to visit, to poke around in their overgrown apple orchards, and then, on the way home, stop in at every roadside antique shop along the way.

But I’ll still be happy to walk out late at night or early in the morning to scope out the neighbourhood for interesting things to salvage.