Reading: The Women’s Patriotic League Cookery Book, 1918

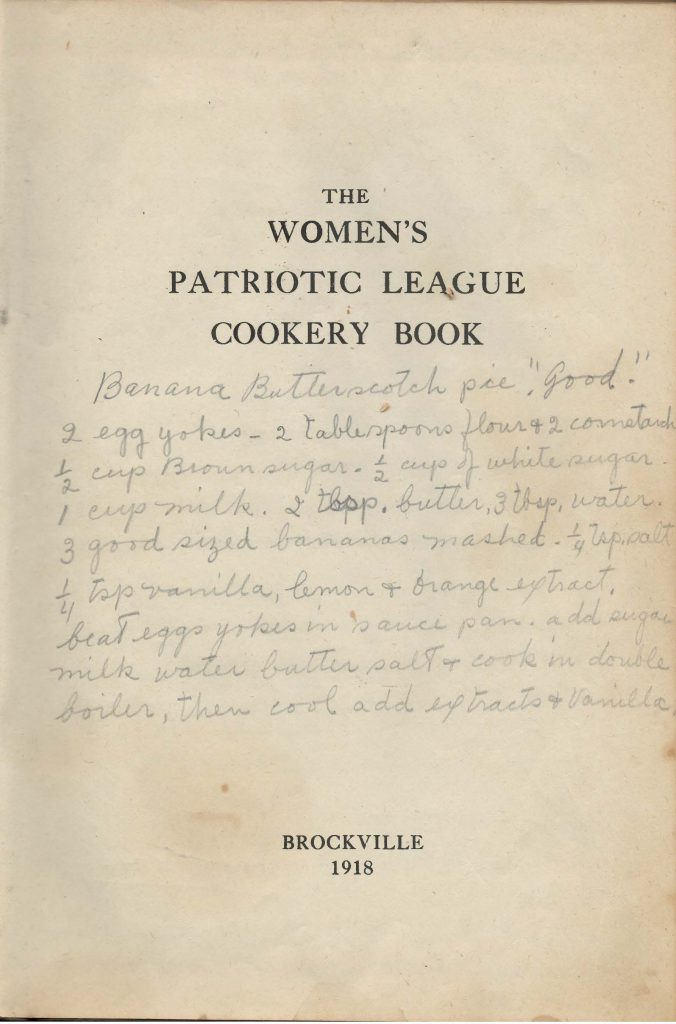

Years ago for a dollar at a yard sale, I bought this well worn copy of The Women’s Patriotic League Cookery Book, published in Brockville (Ontario, Canada) in 1918.

1918 was the final year of the First World War and the cookbook, according to its publishing note, was produced “for the benefit of Red Cross Work.”

During the First World War, Women’s Patriotic Leagues sprung up in cities and towns across the British Empire; in Ontario, there was also a Six Nations Women’s Patriotic League, funded by the Grand River Territory in support of the allied war effort. Women’s Patriotic League activities focused on direct and indirect war efforts ranging from knitting socks for soldiers, fundraising for Red Cross activities, educating housewives about food conservation, supporting families whose loved ones were fighting overseas, and maintaining morale in war-wearied regions.

My cookbook, which sold for $1 in 1918, is filled with “tried and true” recipes standard for the era. But it also has features that make it unique.

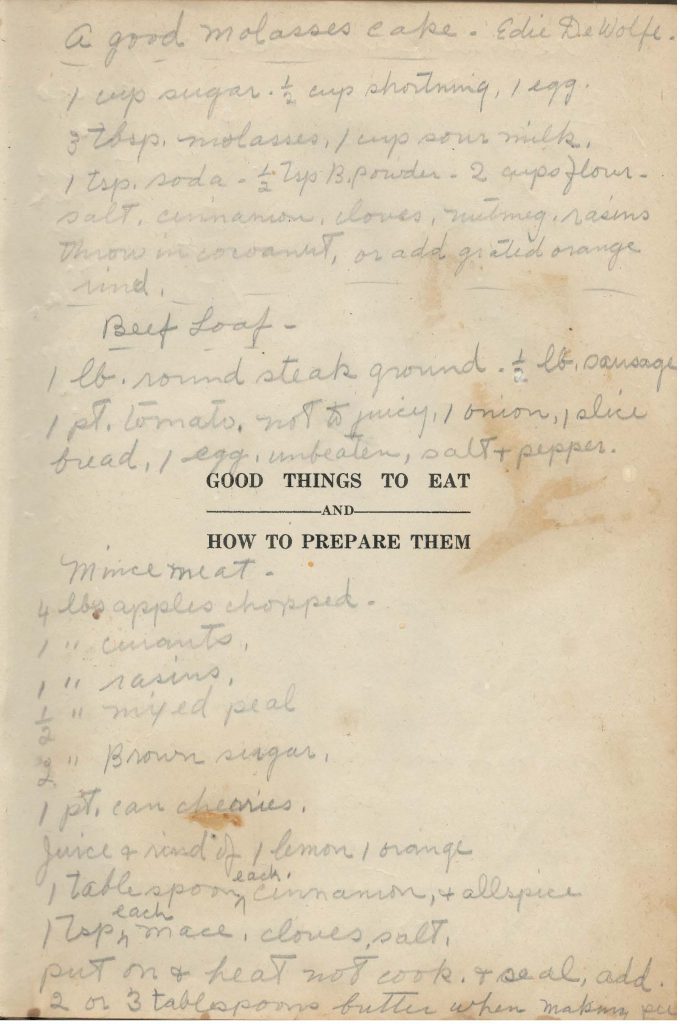

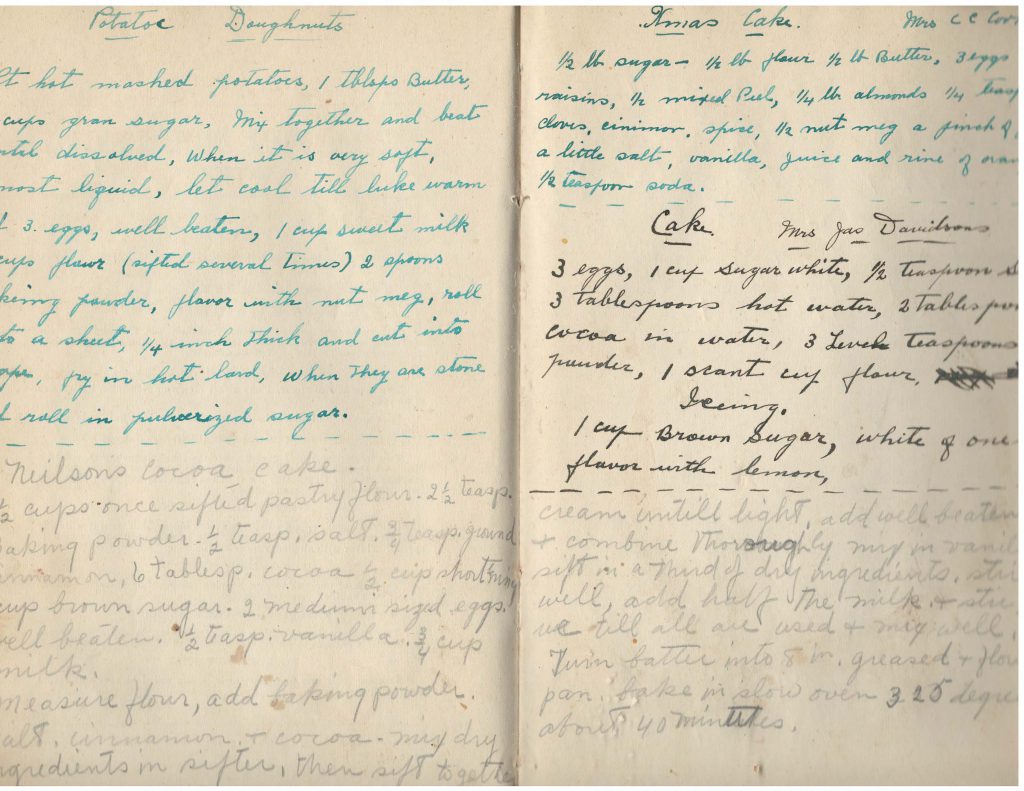

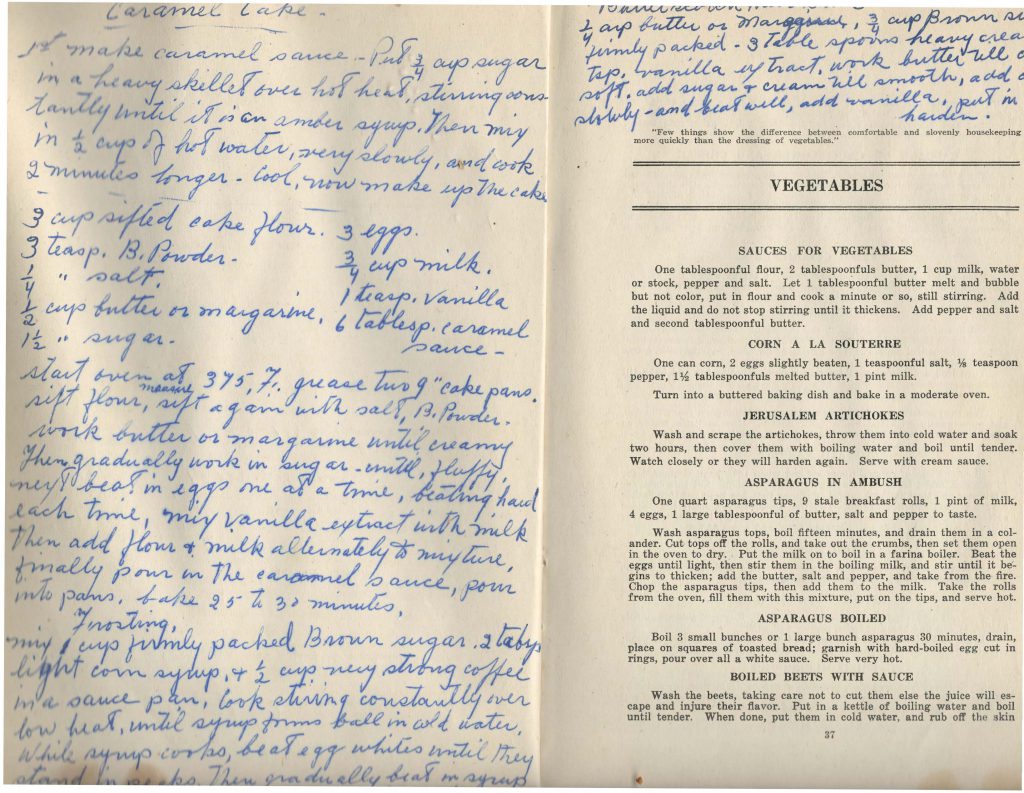

First, my copy includes numerous handwritten recipes, most in pencil but a few in black or blue ink. This is a cookbook collector’s dream: to find a handwritten record indicating how the book was used, and when, and by whom. My book has no owner’s name, unfortunately, but the names of many of the women who supplied the recipes written in by hand are included; e.g., “Mrs. garland’s [sic] drop cookies,” “Edie De Wolfe” (“A good Molasses Cake”), “Blanche’s ice box rolls,””Lemon pudding – Stella’s,” “Mrs. C. C. Cooke” (“Xmas Cake”), “Mrs. Jas Davidsons” (“Cake,”) “Aunt Cecha’s [??] Cookies,” “Marie McWilliams” (“Tomato Sandwich Filling”), etc.. Researching these names would almost certainly help indicate how they were connected, likely through a church or other community network in the Brockville or Leeds County region of Ontario.

The handwritten recipes, which list specific oven temperatures suited to the use of an electric range with thermostat (there are also two handwritten “icebox cookie” recipes), also indicate that this book was likely updated by hand for at least two or three decades, even as technological changes may have made some of the 1918 instructions (e.g., “bake in a moderate oven”) seem dated.

Nearly all the handwritten recipes are for desserts or pickles, and as a result it seems hardly surprising that the printed pages with bread, cake and pickle recipes are the ones that appear most used, at least judged by spills and annotations. A few of the printed recipes in other sections have checks beside them, indicating they had been tried and approved, and others have handwritten annotations and substitutions. But for the most part this cookbook reads like a compendium of community events and social gatherings at which fancy cakes–and their recipes–would have been shared.

A second feature of this cookbook that stands out is the section of War recipes, mainly involving substitutions for white flour and refined sugar. The section is prefaced by the following rhyme–

“If you would be healthy, wealthy and wise,

Eat less meat, waste less wheat,

Cut down on sugar and pies.”

–intended, presumably, to bring food conservation beyond the immediate imperatives of supporting the war effort and into the broader domain of frugality and physical health.

There is a lengthy introductory text in the War Recipes section summarizing some important procedural differences between bread made with white flour and baked items made with whole wheat, rye, oat, barley and rice flour or meal, or with potato (mashed or in starch form). It is an intriguing read a century later, at a time when alternative flours are appreciated for their nutrient advantages and lower glycemic index numbers. Indeed, the 1918 recipe for Sweet Potato Muffins (flour, baking powder, salt, mashed sweet potatoes, milk, water, egg) reads like a pared-down version of this contemporary recipe produced by the Canadian Living Test Kitchen in 2009!

The War Recipes section also includes a recipe for Canadian War Cake, which appears to be a simplified fruit cake:

Canadian War Cake

One cup brown sugar, 1 cup water, 1 1/2 cups seeded raisins, 2 tablespoonfuls lard, 1 teaspoonful cinnamon, 1/2 teaspoonful cloves, 1/2 teaspoonful salt.

Boil together for five minutes and cool. When cold stir in 1 teaspoonful soda dissolved in a little warm water. Add two cups flour sifted with 1/2 teaspoonful baking powder.

Baking instructions are not indicated, but I am guessing this is a cake that would be baked in a “moderate oven” for 25 minutes, in keeping with the other recipes.

In all the years I’ve owned this cookbook, I have never yet baked from it. But a surprising number of the recipes seem strikingly current, and when there is time during the summer, I plan to test out a few, such as this one:

Fried Egg Plant

Cut a nice egg plant in thin slices, lay in salt water two or three hours, then steam until tender. Make a better of 2 eggs, 1 teacupful sour cream, 1 teaspoonful salt, 1/2 teaspoonful soda and flour to thicken. Dip the slices of egg plant into the batter, fry till a light brown in boiling lard. Serve hot.

I might even, I suppose, give Canadian War Cake a chance.

The Women’s patriotic League Cookery Book is reportedly a hard-to-find book in print, but for those interested, the complete text is available online here, thanks to Archive dot org and the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto.

[Text and images not to be reused without permission and attribution.]

Reading: The Women’s Patriotic League Cookery Book, 1918 Read More »