A Return to my Salad Days

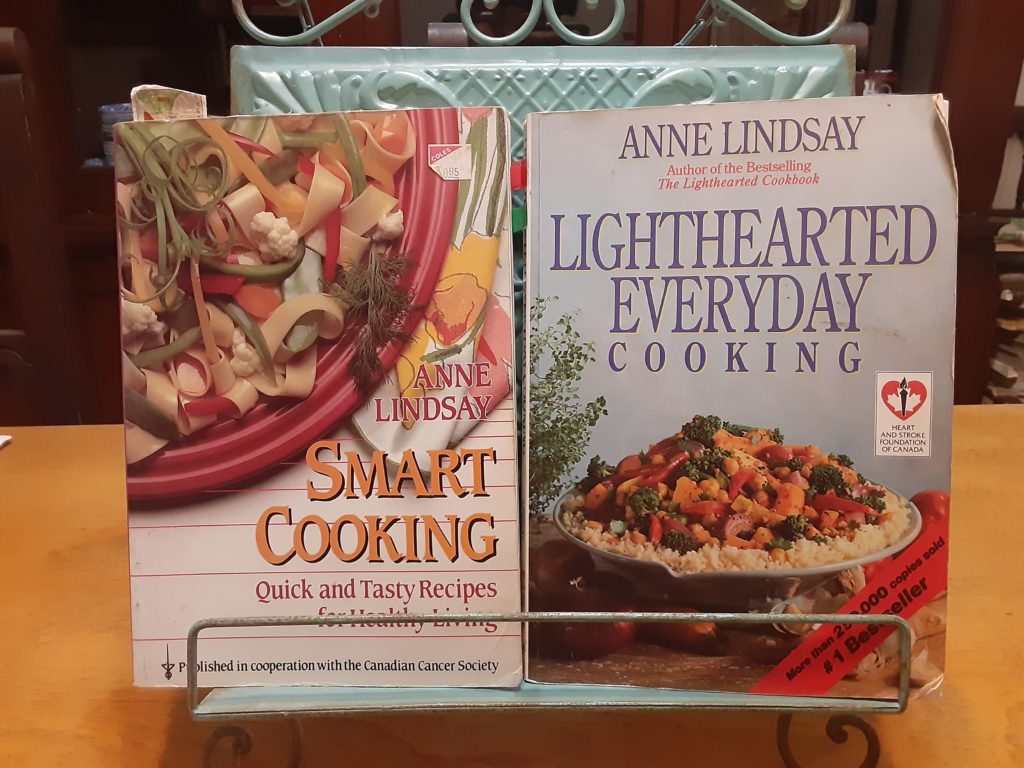

When I first moved away from my parents’ home in the 1990s, I spent a summer buying basic household items at eastern Ontario yard sales. Dinnerware, mixing bowls, a giant sunflower print … and cookbooks. Nearly all these things are long gone—the giant sunflower print, having hung in various narrow apartment kitchens and then in our basement stairwell, finally went out to curbside a few months ago after a quarter century of service—but I still have two of the first cookbooks I ever bought: Anne Lindsay’s Smart Cooking (1986) and her follow-up, Lighthearted Everyday Cooking (1991).

When I first moved away from my parents’ home in the 1990s, I spent a summer buying basic household items at eastern Ontario yard sales. Dinnerware, mixing bowls, a giant sunflower print … and cookbooks. Nearly all these things are long gone—the giant sunflower print, having hung in various narrow apartment kitchens and then in our basement stairwell, finally went out to curbside a few months ago after a quarter century of service—but I still have two of the first cookbooks I ever bought: Anne Lindsay’s Smart Cooking (1986) and her follow-up, Lighthearted Everyday Cooking (1991).

In the eighties and nineties, Anne Lindsay was a Canadian household name. A longtime home economist and food writer for numerous Canadian publications who was named to the Order of Canada in 2003, she partnered first with the Canadian Cancer Society and, later, the Heart and Stroke Foundation to produce cookbooks featuring healthy recipes geared to reducing diet-related disease risks. In keeping with the understandings of the era, the recipes were lower in fat than many contemporary recipes—although, as Lindsay herself has noted, they were not usually low fat. Lindsay’s balanced approach to fats was a prescient choice, given subsequent medical research finding that a balanced intake of carbohydrates, proteins and unsaturated fats is the cornerstone of a healthy diet.

My interest in Anne Lindsay’s cookbooks was not so much dietary (although in those days I was, like most young women of my generation, usually trying to lose weight) as being about developing a basic recipe repertoire. I did, of course, like that the recipes were healthy, but even more than that, I appreciated that they were simple and unadorned. They used ingredients that even I, on a grad student budget, and living in an area with limited grocery options, could find and afford.

Two of the early recipes I learned from Anne Lindsay remain standards in my household: chick-pea salad with red onion and tomato (from Smart Cooking), and red bean salad with feta and peppers (from Lighthearted Everyday Cooking). After all these years I no longer need to consult the cookbooks to make these salads, but for some reason I almost always haul the books out and prop them open on the counter. I have adulterated both recipes over the years (I add avocado and often fusilli to the chick-pea salad, and always make the red bean salad with red cabbage and dried hot peppers) but they remain essentially as Anne Lindsay intended them: straightforward, healthy, and delicious.

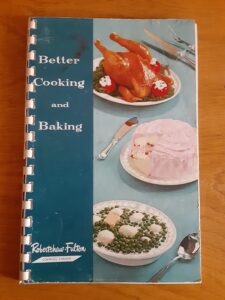

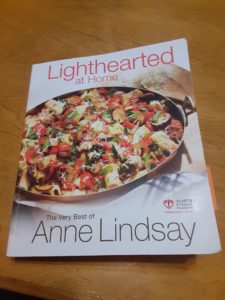

Earlier this week while out running errands, I stopped in at a thrift store to look at (among other things) the cookbooks. Among dozens of discarded paleo, vegan and celebrity cookbooks (one can always trace the downward trajectory of dietary fads and celebrity chefs’ careers by the appearance of their related cookbooks in thrift stores) was a ‘new’ Anne Lindsay cookbook: Lighthearted at Home (2010). I pulled it out and assessed the book, wondering whether it was worth adding to my already burgeoning cookbook library.

Earlier this week while out running errands, I stopped in at a thrift store to look at (among other things) the cookbooks. Among dozens of discarded paleo, vegan and celebrity cookbooks (one can always trace the downward trajectory of dietary fads and celebrity chefs’ careers by the appearance of their related cookbooks in thrift stores) was a ‘new’ Anne Lindsay cookbook: Lighthearted at Home (2010). I pulled it out and assessed the book, wondering whether it was worth adding to my already burgeoning cookbook library.

Unlike a lot of the cookbooks I see (and buy) these days, Lighthearted at Home is not filled with glossy food-porn pictures. The recipes are plain and unadorned. But as I flipped through the book (at 486 pages it’s a hefty compendium), a feeling of something like solid familiarity filled me. “I could make this for dinner tonight!” I said about one recipe after another. “I already have all these ingredients in the fridge!” So with real regret I put Crissy Teigen’s Cravings back on the shelf and brought Anne Lindsay home instead.

I must pause here to note that I love fancy food-porn cookbooks. I love their glossy pictures. I love the long preambles to the recipes. I love the stories about how the recipes came to be, especially when they involve travel to the south of France or anecdotes about the author’s Kurdish grandmother. I love hearing about the glittering dinner parties where these dishes have held centre stage. I love to imagine the glittering dinner parties at which I will serve all these delectable dishes.

The problem is that between Covid lockdowns and three years of 24/7 caregiving to someone with dementia, there haven’t been a lot of dinner parties in my life lately. The days when we catered our own wedding reception, and hosted midsummer garden parties for years thereafter—those days are long past.

It’s tempting, now that the pandemic is over, and with our elder in long term care, and especially after having redone our dining room, to send out invites, plan table settings—and haul out the most lavish recipes I can find.

But I’m busy, and tired, and sometimes think I’ve forgotten how to cook food. Real food, not the delicious but hours-long effort of making, say, the Barefoot Contessa‘s roasted eggplant parmesan (worth every minute, by the way). Real food, not hot dogs and Caesar salad, which were the only foods we could get my mother-in-law to eat in the last months before she went into long term care. Real food I could make for dinner any night, without a great deal of fuss—real food I could even make tonight. Anne Lindsay’s cookbooks fit the bill perfectly.

Tonight, for example, I am going to make pasta with sweet peppers, cheese and basil from Lighthearted at Home. It’s a simple, straightforward, healthy recipe that doesn’t take long to prepare, of the sort one could make any weeknight while casting about for something to cook. It reminds me of the recipes and ingredients included in meal delivery kits (which may well crib their offerings from cookbooks like this one). It’s almost a stretch to call it a recipe: just pasta, some vegetables, some cheese, olives, and some herbs. Lindsay recommends serving this dish with broccoli or green beans; I think it would also be great with chicken on the side. I think this dish would also be excellent as next-day leftovers chilled in the fridge, by which point it would be more like a salad (I have a thing for salads, in case this is not already obvious, and am happy to call almost any chilled leftover a salad if it has any vegetable matter in it at all).

No, it’s not exciting. But this dish, this cookbook, and Lindsay’s entire oeuvre, is ideal for when you are either starting out and don’t know what to eat, or have been making dinners for so many years you’ve run out of ideas, or have glutted yourself on so much food porn you’ve forgotten how to cook the basics.

Update: Here’s tonight’s dinner! I wilted in some fresh spinach greens, because I love spinach and throw a few handfuls of it into just about everything. I also stirred some dried hot pepper flakes (from Apache peppers grown in our garden) in with the onions while they sautéed. I should have saved a cup of pasta water to stir in for extra creaminess. And maybe poured in a glug of red wine vinegar, just to take Lindsay’s recipe, already half Greek with the feta and Kalamata olives, the rest of the way (and, if so, I would substitute oregano for the basil).

This is the great thing about this kind of recipe: you can add or substitute ingredients to suit your preferences (Lindsay encourages this very thing) but always have, at base, a solid recipe you can count on to get something good to the table any night of the week.

A Return to my Salad Days Read More »