A Read of The Girl’s Own Annual (1907-1908) and an Inadvertent Critique of Goodnight Stories for Rebel Girls (2016).

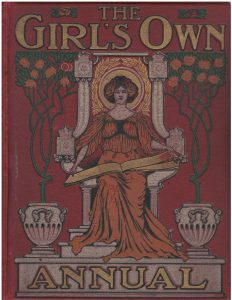

At the 2018 University College book sale I bought this 1907-1908 volume of The Girl’s Own Annual, a bound compilation of the preceding year’s weekly issues of The Girl’s Own Paper.

At the 2018 University College book sale I bought this 1907-1908 volume of The Girl’s Own Annual, a bound compilation of the preceding year’s weekly issues of The Girl’s Own Paper.

The Girl’s Own Paper was a weekly and, later, monthly, publication produced between 1880 and 1956 for older girls and young women. Its founder and first editor, Charles Peters, is described as having sought “to foster and develop that which was highest and noblest in the girlhood and womanhood of England.” After Peters’ death late in 1907 (an In Memoriam is printed in the 25 January 1908 edition of the Paper); his successor, Flora Klickmann, saw the Paper through the First World War and the important social changes that followed, including women’s suffrage. Scholarly work on The Girl’s Own Paper notes that Klickmann’s editorial influence became apparent early on, especially in the form of an increasing (if somewhat ambivalent) emphasis on the changing roles of women in the early decades of the twentieth century.

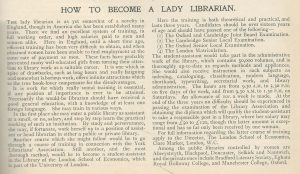

At the same time, even under Peters’ directorship (at least in the volume I have), women, their lives, well-being, interests and work are valorized in ways that seem to go beyond commonly received late- and post-Victorian notions of the proper place of women. I found it both a surprise and delight, for example, to discover an article titled “How to Become a Lady Librarian” in a 1908 issue of the paper. The article notes the scarcity of training and opportunities for women librarians in England, and laments that even well trained women “have been unable to find employment at the same rate of payment as men.” It goes on to indicate the proper rates of pay women librarians may reasonably expect, and makes suggestions about where to obtain training, including at the London School of Economics. At its close, the article lists “public libraries controlled by women,” among them Manchester College at Oxford.

notes the scarcity of training and opportunities for women librarians in England, and laments that even well trained women “have been unable to find employment at the same rate of payment as men.” It goes on to indicate the proper rates of pay women librarians may reasonably expect, and makes suggestions about where to obtain training, including at the London School of Economics. At its close, the article lists “public libraries controlled by women,” among them Manchester College at Oxford.

“How to Become a Lady Librarian” is far from the only article offering career advice. “A New Employment for Women” offers recommendations on obtaining training and suitable employment for teaching hearing impaired children. It also indicates the salary range a qualified teacher may expect to be paid. Another article, “A Strange College for Women Workers,” describes bee farming in detail, including set-up costs, and observes, “[i]t would take more nerve than the average “mere man” possesses to allow from 25,000 to 30,000 bees to roost on his bare arm and make themselves at home; any yet, at the Luton Bee College, women students think nothing of this performance.” “How I Became a Lady Doctor” describes one woman’s progress into the profession; in it the author, Doctor Penelope Smith, concludes that the greatest difficulty facing qualified women doctors is not ability but unequal access to hospital experience: “To gain a wide experience hospital practice is absolutely necessary,” she writes, “and it is in the deficiency of opportunities for this practice that women are placed at a disadvantage as compared with men; not in the training, nor in their capabilities for mastering the details of their profession.” An essay on portraitist and illustrator Marcella Walker describes her work (exhibited at the Royal Academy, reviewed in the Academy Review and published in the Illustrated London News) as a rebuttal to those who “assert that women have no originality, and merely follow and copy men in art.”

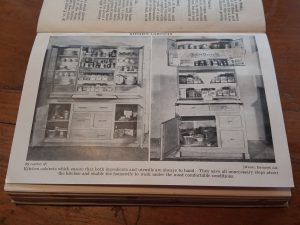

The volume is still, of course, evocative of its era. Young women are urged to take care of their skin, lest it become reddened and wrinkled with work. Readers are invited to participate in physical activity, but (horrors) not in any way that might masculinize them. An otherwise charming illustration of a woman playing field hockey, for example, has the admonition captioned to it: “Avoid all excess in the field games which are suitable only to sporting men.” Every woman pictured is white (although The Girl’s Own Paper was circulated throughout the Empire), in good health, and visibly representative of her upper class (or upper class-aspiring) upbringing. The amassing of a “White Trousseau” receives treatment in a number of issues, as does an ongoing series called “How a Girl Should Dress” (properly, with full skirts and gloves and enormous hats; restrictive, and yet: how I long to have at least one similar costume).

While browsing the Annual, I have felt wistful for two reasons. The first is that my mother would have loved it. We shared a fascination with the sometimes ephemeral traces of everyday life found in old newspapers, letters, paper crafts and magazines, and would spend hours poring over all these sorts of documents whenever they came to light. This Annual is one of the richest such resources I have encountered in years, and I wish so much that we could share it. She would have loved the quirky essays (and their quirky titles), like “Methods of Travelling Used by Women from Early Times Down to the Present,” “Fire-Lighting Without Sticks,” “Insects Mentioned in Shakespeare,” “Familiar British Seaweeds,” and perhaps especially, “Book-Binding for Girls.”

The second reason I feel wistful while reading the Girl’s Own Paper is because, despite its implicit snobbery and adherence to vastly outdated conventions, there is also something empowering in the articles and stories in its pages. Women, it says repeatedly and in many different ways, have value. Women’s pursuits and work have worth, whether they involve sewing, cooking, writing, playing music or caring for others–or pursuing higher education and working in demanding fields. An older girl or young woman reading its pages would have reason to feel encouraged, not only by the things articles suggested she could do if she chose, but by the histories of other women who have done them, too.

Annuals featuring improving stories for girls have fallen mostly out of favour, even in the United Kingdom where they could once make a publisher’s year, but some months ago I received a copy of Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls (Penguin Random House, 2016) to give to my daughter. The book was received with wild enthusiasm by reviewers, spurring a sequel, but in our household it was met with a muted “meh.” The book is subtitled “100 Tales of Extraordinary Women,” and this, I think, is at the heart of the book’s problem. It is not that the women profiled are not extraordinary, and it is not as if this kind of book is not desperately needed: it is.

But even its dedication makes demands of its young readers: to be rebels, first of all. And immediately afterward, it suggests that the things girls do already are not enough: they must “dream bigger, aim higher, fight harder,” and live with the conviction that they are “right.” Most of the women profiled in Rebel Girls are wonderfully chosen, and I do love the profile of American Supreme Court Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg. But the narratives return, over and over again, to how extraordinary they were or are, and how unusual their accomplishments. Very few of the narratives directly invite the reader to consider herself capable of doing the same kinds of things. Sadly but perhaps revealingly, one of the few stories that does so is the one about Virginia Woolf, which discusses her depression and acknowledges the possibility that even rebel girls might sometimes be sad. Sudanese supermodel Alek Wek is quoted as saying, “You are beautiful. It’s okay to be quirky. It’s fine to be shy,” — but her important message seems to be drowned out by so many injunctions in the other stories for girls to be aggressive, competitive and attention-seeking. After 200 pages of superlatives, the reader is, at last, invited to “write your story,” but it seems to me that by this time, after so many pages of genius, originality and victory, especially those in which systemic barriers to women’s flourishing are subsumed beneath narratives of individual strength, more than a few readers might feel deflated. I certainly did, and I am an exceedingly determined person who has been standing for something for nearly three decades. My daughter liked the book, but found the stories hard to relate to.

Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls reminds me of the response to the 2016 all-woman remake of the popular 1980s film Ghostbusters. Although the remake was fun to watch, it was essentially mediocre; basically on par with most remakes, and slightly better than a typical sequel. But public response tended to be sharply divided between those (whose testicles seemed to shrivel at the sight of a woman wielding a proton pack) who insisted it was the Worst Film Ever, and those (mostly women) who insisted upon its virtues. It seemed impossible for anyone to simply say out loud that it was a fun but essentially mediocre remake–because women in film, like women in public life, cannot afford to be mediocre.

In this context, the overwrought exhortations of “extraordinary” women’s greatness in Rebel Girls seem to me to undermine the book’s very good intentions. Indeed, ultimately the book’s message seems somehow indistinguishable from diet and ‘wellness’ marketing campaigns exhorting girls and women to be ever thinner, sexier, more feminine–and ever more obedient to always arbitrary, always external injunctions about how they must look and live. It seems to me, especially in the era of the ‘crisis of the mediocre man,’ that women should not always have to overcome the social (and political and economic) deficit of being women in a sexist society by being deemed geniuses, heroes, winners or leaders. Very good women actors should be able to star in mediocre films. Ordinary girls and women should be counted, too, whether they are ‘rebel girls’ or not.

This is something, oddly enough, that The Girl’s Own Paper seems to have gotten right more than a century ago. Despite its conventionality and essential conservatism, its pages reinforce the perspective that every girl, and every woman–not only those deemed “extraordinary”–is special and has worth, and that every girl and every woman has the capacity to stand up for herself, and for others, and has the right to contribute to both private and public life and to make herself heard in both worlds.

I suppose I am hopeful that the Rebel Girls franchise will eventually get to the point of unpacking some of the contradictions in its narratives. On the way, its authors could do worse than read a century-old volume or two of The Girl’s Own Annual.